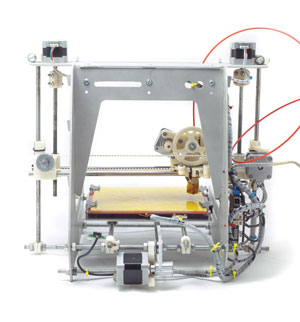

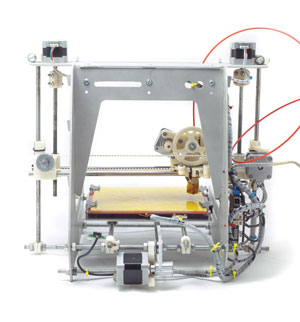

For a long time, 3-D printing seemed like the stuff of science fiction. But the technology has progressed so far that anyone in Toronto with a library card can now rent one out.

While they’re still far from being a fixture in everyone’s home, 3-D printers have become cheaper and easier to use, causing many intellectual property lawyers to begin considering the implications of a world where everyone can print out physical objects in their basements.

Aaron Edgar, a lawyer with Edgar Chana Law, says 3-D printers first came to his attention a few years ago. “I kind of followed the MakerBot stuff,” he says.

“It seemed kind of interesting, but at the same time, what am I going to use these small plastic pieces for?”

Today, some of his clients use 3-D printers to create prototypes, but they involve very expensive machines that are well outside the price range of the average person.

Tony Edwards, a partner at Field Law in Calgary, says the improvement in 3-D printed objects has been quite remarkable.

“The quality of the materials has really significantly changed,” he says. “When they first showed up, they were as fragile as egg shells. You could look, not touch.”

As the quality of 3-D printed objects increases and the price of printers decreases — the cheapest MakerBot printer costs around $1,400, for example — there’s a risk the devices will become to physical objects what the Internet and file-sharing were to digital ones. Many people are already envisioning a future where computer-aided design drawings of objects with intellectual property protections are available illicitly online, allowing people to print them out at home.

This scenario presents a problem for those who hold the rights.

“If someone is in their basement producing a widget that infringes your patent, is the rights holder ever going to know about it? Likely not,” says Tim Bailey, an associate at Field Law.

And even if they do find out, companies and individuals who are having their intellectual property rights infringed may not want to pursue litigation.

“I think the industry has learned a lot and that the bad press may not have been worth it,” says Edgar, referring to the experiences of the music and film industry when file-sharing first became ubiquitous.

Today, most companies go after people who are illegally distributing copyrighted items on a large scale online instead of the end users. Would that same strategy work for patented objects as well?

Edwards says that since Canadian patent law is only applicable in Canada, it would be very difficult for those who hold patents to enforce their rights if the person distributing the material is offshore.

“Patents may not be the heavy-handed weapon which people ordinarily think it would be,” he says.

Instead, Edwards thinks companies will be better off pursuing copyright claims against the people distributing their designs.

“If you look from the rights-holder perspective, the main big gun is copyright,” he says.

But one of the biggest challenges for intellectual property holders will be to simply figure out who’s infringing on their rights.

“It’s kind of an academic conversation about enforcing rights if you can’t actually start a lawsuit against the infringer,” says Laura MacFarlane, also an associate at Field Law.

MacFarlane says one tool that would be useful to parties would be a Norwich order, a discovery mechanism allowing a party to compel an Internet service provider to reveal the identity of someone who’s linking to infringing material that could give rise to a potential lawsuit.

“This can sometimes be a complicated two-step process where you have to first obtain an order to just get the IP addresses used by the infringer and then obtain a second order to compel that Internet service provider to disclose that information linked to the IP address,” says MacFarlane.

However, Internet service providers don’t have to retain that type of information for any length of time, so those who hold the rights have to act quickly.

Edwards thinks the first targets for large-scale 3-D printing infringement will be high-value items such as designer sunglasses or BMW key fobs. But he notes it’s possible to print all sorts of things using 3-D devices.

“Food has been 3-D printed,” he says.

“Leather has been 3-D printed. So it’s no longer the rigid objects that everyone assumed. You get into the 3-D printing of food and imagine the regulatory problem you’ve got there.”

But Bailey says most of the best practices for companies when it comes to responding to issues related to 3-D printing will be the same as for those dealing with more mundane sorts of infringement.

“We regularly advise our clients to maintain surveillance of their own intellectual property portfolios, whether that be patents, trademarks, copyrights or industrial design,” he says.

“Ensure that registrations are made regularly and on time. That helps establish ownership of the intellectual property right. We also advise our clients, particularly our corporate clients, to ensure that they have a clear chain of title [for] any employees that may have participated in developing the intellectual property.”

Despite the hype, Edgar is skeptical of the idea that 3-D printing will take off in the same way file-sharing did.

“I think it’s one of those things that time can tell but I don’t think it’s going to be as big a deal as people in the media make it out to be,” he says.

“It takes specialized expertise and it’s not the easiest thing to do.”

While they’re still far from being a fixture in everyone’s home, 3-D printers have become cheaper and easier to use, causing many intellectual property lawyers to begin considering the implications of a world where everyone can print out physical objects in their basements.

While they’re still far from being a fixture in everyone’s home, 3-D printers have become cheaper and easier to use, causing many intellectual property lawyers to begin considering the implications of a world where everyone can print out physical objects in their basements.