The court has ordered a group of condominium directors to personally pay costs of almost $100,000 for acting in bad faith in a dispute over a landscaped courtyard.

With more and more property buyers snapping up condos as they spring up across the province,

Boily v. Carleton Condominium Corp. 145 provides a cautionary tale to owners who volunteer as directors and make controversial decisions.

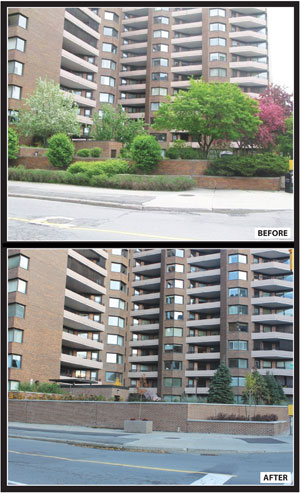

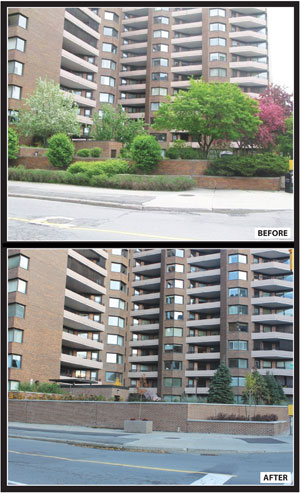

The dispute started when a group of residents at a condominium in Ottawa objected to changes proposed by the board of directors to a landscaped courtyard.

The owners complained that the redesign would result in less greenery and more parking and constituted a “substantial change to the common elements” requiring the approval of two-thirds of the owners under the Condominium Act.

But the board of directors said the changes only amounted to maintenance work and required a simple majority vote at most. The owners obtained an injunction stopping the board from holding a meeting on the issue or carrying out work until the court had issued a ruling.

The board and owners reached a settlement after agreeing that a decision on the design and appearance of the courtyard would go to a two-thirds vote. At the meeting, the board didn’t obtain enough support and took the position that there had been no agreement.

The owners brought a motion to enforce the settlement and on June 29, 2011, Superior Court Justice Robert Beaudoin ordered the board to honour the agreement. He also told it to return the courtyard to its original appearance as work on it had already begun. However, the directors ignored the direction and pressed on with work that deviated from the original courtyard design.

They said they were in the position of having to undertake significant structural repairs without adequate provisions in the reserve fund established by previous boards. They also felt the complaints about the landscaping project had sprung out of a desire by the applicants to remove the board.

On March 8, 2013, Beaudoin found the directors and the corporation to be in contempt of his court order. The directors had “breached the order wilfully and deliberately” and acted “neither honestly and in good faith, nor as a reasonably prudent person,” the decision stated.

They also failed to seek advice from their counsel before acting, and, in returning only a small portion of the courtyard to its former state, had taken a “narrow and self-serving view” of the previous order.

Beaudoin told them to personally pay the costs of reinstating the courtyard to the way it was before the changes.

In a surprise costs decision on April 29, 2013, the judge then ordered the directors to personally reimburse the owners’ legal fees to the tune of $96,800.

“Their stubborn refusal to accept the applicants’ success set them on a path of deliberate and continual contempt that should attract a costs award on a substantial indemnity basis,” he wrote.

It will be up to a majority of unit owners to decide whether the condo corporation should be reimbursed for any legal fees paid on their behalf. However, Beaudoin said the owners who brought the proceedings must be exempt from any condo charges associated with the directors’ fees.

Evidence filed in court suggested the directors had paid fees of about $106,000 from the board’s reserve fund.

“What’s interesting is that the court has imposed personal liability on directors of a corporation,” says Rodrigue Escayola, a partner at Heenan Blaikie LLP and counsel to the condo owners.

The Condominium Act provides

considerable protection to board directors for good reason, he suggests. “Directors act as volunteers.

It’s a lot of work and they have to face a lot of tough decisions on a daily basis. You’re stuck between owners and legal obligations. Every owner wants the lowest amount of condo fees but also the highest level of service possible.”

But the protection relies on directors acting in good faith under s. 37(b) of the act. Escayola says the courts are increasingly taking the line that those who fail to act in good faith will have to shoulder the financial burden of their actions.

Despite that fact, the Carleton directors are appealing the finding of contempt and the costs decision. They’re also seeking an order that would force all owners to pay for the reversal of the changes to the garden.

“In my view, they have a very tough appeal battle,” says Escayola. “It’s a very unusual finding,” says Sharon Vogel, a partner at Borden Ladner Gervais LLP.

“There’s a lot of interest in the case. It’s unusual to see a case where a board of directors is found personally liable for costs as opposed to the corporation.”

She’ll be advising boards of directors to look “very closely” at s. 97 of the Condominium Act that deals with the situations requiring two-thirds approval to make changes.

The case also demonstrates the need for directors to seek and act on professional advice in order to avoid accusations of acting in bad faith, she says, adding that in the long term, the decision could lead to more owners taking directors to court.

The need to create “mechanisms” for unit owners to ensure that directors don’t act in bad faith is “part of the motivation behind the push to change the Condominium Act,” she suggests.

“It’s a difficult act to work with right now. For unit owners who disagree with something the boards are doing, it’s a cumbersome and difficult process [to take action]. Taking the board to court is time-consuming and expensive.”

The government is reviewing the act through a three-stage process overseen by Ontario’s Ministry of Consumer Services. The current legislation came into effect more than a decade ago before the dramatic condo boom that followed. Condominiums now account for almost half of new homes built in the province and about 1.3 million Ontarians live in one.

A report published in January after the first stage of the consultation highlighted governance disputes as one of the main areas requiring fresh guidance. The report called for “a more effective and efficient means to enforce the rules and responsibilities set out in the Condominium Act” and said boards of directors need training and support.

Mediation tools will likely “need to be incorporated into a more effective dispute resolution system for the future,” it added. Many involved in the consultation also called for an independent organization to oversee the new system.

But it also found owners needed to take greater responsibility for the good governance and management of the community.

Escayola agrees, arguing that any additional powers granted through the revised act must not favour one side.

“The legislation is based in such a way to protect owners, and to protect owners you need to give powers to the corporation,” he says. Such powers could include imposing a lien or being able to seize money owed to the corporation by “delinquent owners.”

Stage 2 of the review is currently underway. It involves condominium experts reviewing the initial findings and the public commentary it generates and developing recommendations to the government.

The report is due to be available for public comment by the end of the summer. People can send their views at any time to

[email protected].

With more and more property buyers snapping up condos as they spring up across the province, Boily v. Carleton Condominium Corp. 145 provides a cautionary tale to owners who volunteer as directors and make controversial decisions.

With more and more property buyers snapping up condos as they spring up across the province, Boily v. Carleton Condominium Corp. 145 provides a cautionary tale to owners who volunteer as directors and make controversial decisions.