The losing party shouldn’t face adverse consequences for failing to file a bill of costs, even when directed by the judge, the Ontario Court of Appeal has ruled in a fractious estates case.

In its ruling this month, the appeal court redirected Ontario Superior Court Justice David Brown to reassess his original decision that ordered Nancy-Gay Rotstein to pay $737,000 in costs and disbursements to her brother, Lawrence Berk Smith.

The Court of Appeal upheld Brown’s decision to award partial summary judgment to Smith related to his mother’s estate and to grant costs on a full indemnity scale. But the 3-0 ruling written by Justice Robert Armstrong found that in determining the appropriate costs, Brown didn’t properly consider a detailed written critique filed by Rotstein’s lawyers that challenged the bill submitted by Smith’s counsel.

“What the motion judge has done is reject an argument based on an analysis of the evidence of billing rates and hours because the appellant failed to file her own bill of costs, which she is not required to do,” Armstrong wrote.

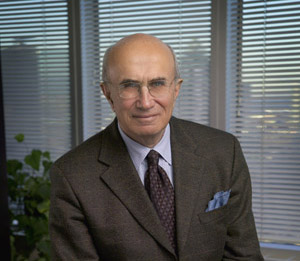

Richard Shekter, lead counsel for Smith, says that while the quantum of the costs still has to be decided, his client is “delighted” with the ruling. “The big fight was whether full indemnity was appropriate. The Court of Appeal said yes,” notes Shekter, a founding partner at Shekter Dychtenberg LLP.

Brown ordered partial probate to Smith in a 1987 will and two codicils drafted by his mother, Ruth Dorothea Smith. She died in 2007 and left an estate with a net value of $1.2 million.

Rotstein was excluded from the will, except for two pieces of jewelry. Rotstein, an author and lawyer, had been estranged from her parents since 1976 due to a dispute over two real estate transactions. The bulk of the estate went to Smith and his children. A third and fourth codicil to the 1987 will provided for varying amounts to one of Rotstein’s daughters.

Smith didn’t seek summary judgment with respect to the funds left for Rotstein’s daughter and agreed to hold back $250,000 of the estate until the parties could settle that issue.

Rotstein filed a notice of objection after her mother died. She alleged her mother lacked testamentary capacity, didn’t have knowledge or approve of the contents of the 1987 will, and was subjected to undue influence.

But Brown found that there was “no air of reality” to the claim that the mother was subjected to undue influence. “There was no justification in law or in fact for Ms. Rotstein to have taken her challenge through to the hearing of the summary judgment motion,” Brown wrote. “To engage in baseless, hugely expensive, scorched-earth litigation over the validity of a will is litigation conduct that falls into the category of ‘reprehensible’ and merits the award of elevated costs.”

What the judge described as “the most extraordinary feature of this motion” was that Rotstein didn’t file a responding affidavit to the motion for summary judgment and declined to provide herself for examination. Instead, Smith’s lawyers cross-examined her husband.

The Court of Appeal agreed that this was an appropriate case to deviate from the “general rule of probate” that all testamentary documents be considered at the same time. It concluded “there is not a scintilla of evidence” that the 1987 will and the first two codicils were invalid. However, a bill of costs in excess of $700,000 invites “careful analysis,” the Court of Appeal stated. “While she may well have paid fees equivalent to or in excess of those claimed by the respondent, she is still entitled to challenge the respondent’s bill as unreasonable,” Armstrong wrote.

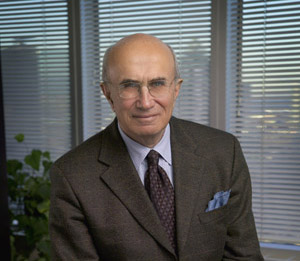

Earl Cherniak, who represented Rotstein on the appeal, says the latest ruling makes it clear that it isn’t mandatory for the losing party to file a bill of costs. The critique of Smith’s bill filed by the lawyers who acted for Rotstein in the Superior Court included “very careful submissions,” says Cherniak, a partner at Lerners LLP.

“The Court of Appeal has told Justice Brown he has to pay more attention to these submissions.”

In its ruling this month, the appeal court redirected Ontario Superior Court Justice David Brown to reassess his original decision that ordered Nancy-Gay Rotstein to pay $737,000 in costs and disbursements to her brother, Lawrence Berk Smith.

In its ruling this month, the appeal court redirected Ontario Superior Court Justice David Brown to reassess his original decision that ordered Nancy-Gay Rotstein to pay $737,000 in costs and disbursements to her brother, Lawrence Berk Smith.