Nibwaakaawin program designed to aid negotiations when Indigenous rights intersect with projects

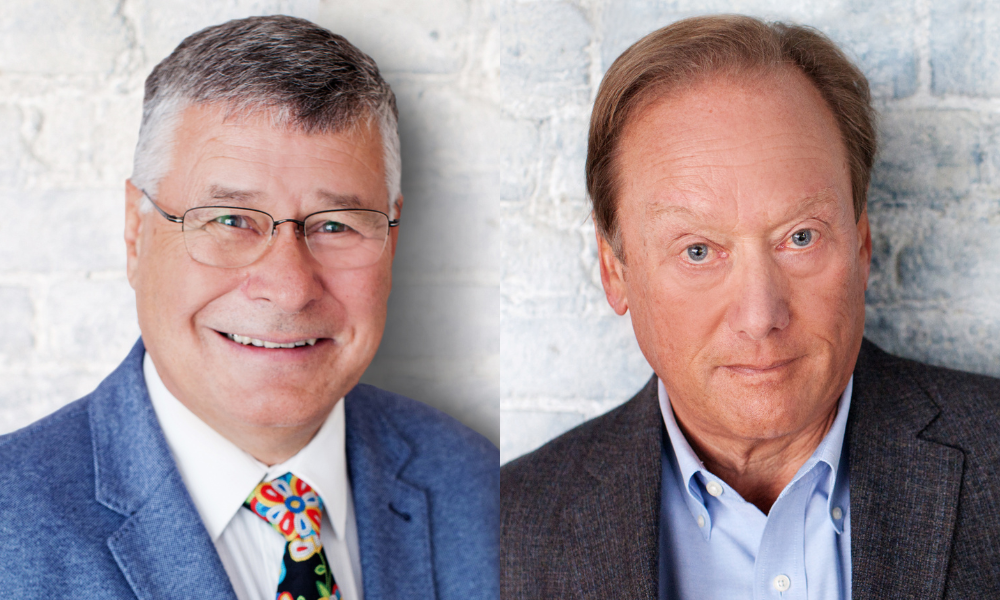

Lawyers who work with clients in engaging with First Nations peoples should be armed with tools to help them and their clients facilitate the process, says John Beaucage, former Grand Chief of the Union of Ontario Indians, and principal at Counsel Public Affairs.

Canadians and others who are interested in working with Indigenous group on projects “are still on a learning curve,” says Beaucage, whose firm has developed a new training program focused on “respectful engagement” with Indigenous communities.

“Many businesses and organizations are unsure of their responsibilities and how to undertake the process of engaging with Indigenous peoples.”

Beaucage says lawyers are a prime candidate for this sort of training, and many clients who need to consult with Indigenous training have indicated an interest in this sort of course.

“Last spring, I was at a conference of the International Association of Mediators, and I gave a speech on consulting with Indigenous peoples. After that speech, about eight lawyers came up to me saying they’d love some sort of training because they need to get a better understanding as they become more involved with Indigenous communities in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Northern Ontario.”

Another time, Beaucage says, he was asked by a vice president of a mining company as to why it needed such training services. “I said ‘Well one of the things it might do is stop you from making stupid mistakes.’ And that in a nutshell is what we’re trying to do.”

While Indigenous peoples are “eager to engage,” Beaucage says they want to be treated respectfully and “meaningfully consulted early on any project that affects their people, land, and rights.”

Training in that process would go a long way to facilitate that respectful consultation, he adds, noting the training can be done in individual sessions or as a series of sessions offered virtually or in person.

Counsel PA’s “Nibwaakaawin” (pronounced nib-wah-kah-win) training program – which means “wisdom” in Ojibwe – is designed to help clients better understand how to negotiate with Indigenous groups whose rights and interests intersect with their work.

Charles Harnick, the founding partner of Counsel PA and the former Ontario minister responsible for Native Affairs (now called Indigenous Affairs), says that businesses and organizations “need to understand” how to engage and negotiate with Indigenous peoples in an “open and transparent way.” Any consultation should also follow the recommendation outlined in the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.”

Harnick adds that when businesses go to law firms with proposals for a project they are interested in pursuing that intersects with Indigenous communities, “lawyers tend to be very good at identifying the legal issues at stake.” But then they must turn to the “nuts and bolts” of how to consult with the First Nations groups involved so that it meets the obligations to consult with them meaningfully.

“So lawyers getting this training would likely find it very useful as they engage with Indigenous groups on behalf of their clients, and to help their own clients understand how to take the right steps to establish a “positive relationship.” He describes the training as “very practical and hands-on,” designed to help lawyers and their clients “go into a situation and build a relationship so that you can move head.”

Says Harnick: “You of course need the legal advice that outlines when and why there is as duty to consult. But once that is determined you need to facilitate that engagement. That’s where our training fits in. To look at how to engage with Indigenous peoples in a in a way that is going to allow compliance with those obligations. And even more important is building a lasting relationship based on trust and transparency.”

Beaucage adds that “one of the first jobs” in any consultation process is to deal with possible infringements of treaty rights on Indigenous land. “I’ve always said that consultation doesn’t begin until the Indigenous community says it begins. And that means Indigenous peoples need to feel comfortable with the process – that it is respectful and transparent.”

As well, Beaucage says he has noticed that there is a lack of knowledge by corporate and government entities when it comes to the consultation process, which is especially surprising given the number of court cases, including those at the Supreme Court of Canada level, that insist on upholding the duty to consult.

Some multinational corporations may want to develop a project in Canada, perhaps for the first time, and governments tell them they must consult, says Beaucage. “So they are starting from scratch. They have no concept of treaty rights, and are working from a blank page, even if they want to do the right thing.”

He points out that there are likely very few pieces of land in Canada with the potential for a mining, energy, or forestry project that “don’t have some kind of imperative to consult with an Indigenous community.”

In establishing Nibwaakaawin to support clients across Canada, Beaucage says Counsel PA is assembling a roster of Indigenous leaders and experts representing First Nations and Indigenous peoples from coast-to-coast. Since treaties, relationships, and provincial governments vary across the country, Beaucage says Nibwaakaawin training is highly tailored to “each client’s needs, knowledge, and context.”