The communities around Toronto are being shortchanged by the distribution of Superior Court judges in Ontario, says a Markham, Ont., family lawyer.

While 91 judges are assigned to the court’s Toronto region to serve a population of almost 2.7 million, the central east region, which includes Barrie, Newmarket, and Oshawa, Ont., gets just 44 judges for a similar combined population.

That means Toronto has one Superior Court judge for every 29,000 people, while central east gets one judge for every 56,000 residents. The central west region, which includes Brampton, Ont., is even worse off with one judge for every 65,000 people. Only in the northeast and northwest regions are the ratios more favourable than in Toronto.

Andrew Feldstein, who practises family law in courthouses throughout the Greater Toronto Area, says the distribution is unfair on his clients who happen to live outside Toronto.

“What you notice when you go to a court like Newmarket, Oshawa or Barrie is that the judges have extremely long lists, whereas if you come to the city of Toronto, there may be four or five items on the docket that day.

Those judges have a lot more time they can devote to work on a resolution of a matter or moving it forward. So the quality of justice you get in Toronto versus other areas is significantly better.”

According to Feldstein, family case conference lists in the central east region can run as long as 12 matters. “That judge is going to have to read 24 briefs a day to be ready for court.

That’s a lot of briefs and a lot of information to bring in. Even with the best of intentions, they’re limited to about 30 minutes per client that comes in. Even a settlement conference will give you no more than an hour because of the lengthy dockets.

How can you take a complex matter and in one hour resolve it? Sometimes you need lengthy periods of time with a judge, and in Toronto they have more time to help people that way.”

In the criminal sphere, lawyer Edward Prutschi of Toronto firm Adler Bytensky Prutschi Shikhman also practises throughout the Greater Toronto Area.

He says the difference between Toronto and surrounding communities is less acute in his area of practice, something he puts down to the nature of the work judges are doing in the provincial capital.

“Often, there’s only seven or eight matters over seven different courtrooms and these are all lengthy projects or homicide cases that are tying up a judge for months and sometimes years at a time, so you can’t use judicial resources in the same way as a smaller jurisdiction that might have a higher proportion of day-to-day, run-of-the-mill cases,” he says.

“Anybody who claims Toronto is over-serviced judicially is wrong. I can say that clearly. What it may mean is that outlying regions are even more underserviced than Toronto. You’re certainly not getting a situation where Toronto judges are sitting around on their hands.”

Feldstein says he’d like a complete review of the allocation of judges and more appointments to the central east and central west regions in particular.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean to me judges need to be permanently assigned there, but in Newmarket, judges need help in order to reduce the lists. Maybe that means bringing in judges from other regions.”

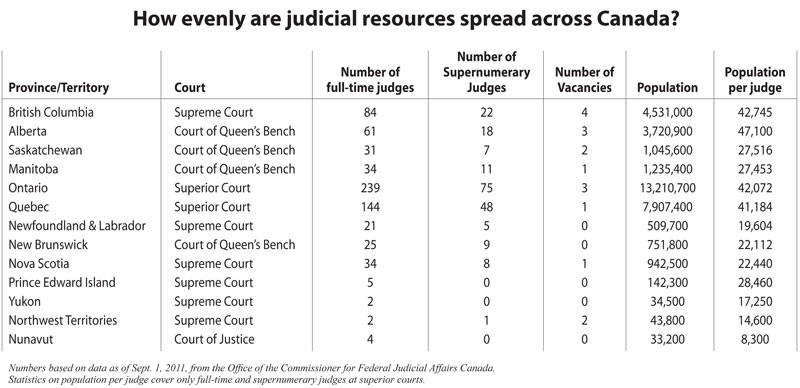

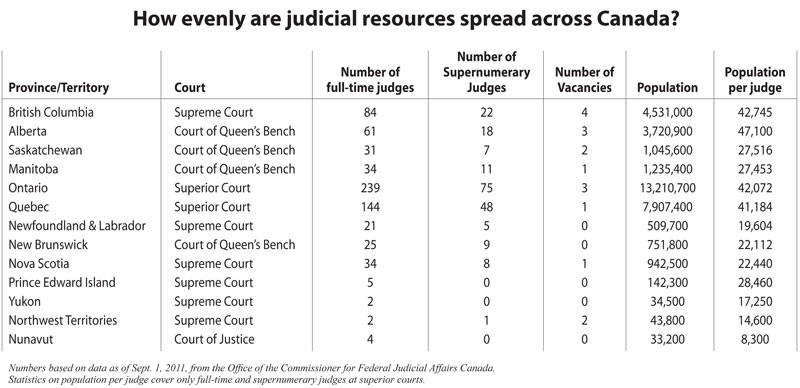

Ontario could make a decent case for more Superior Court judge appointments from the federal government since national statistics show it has 42,072 people per judge. That number is higher than all other provinces except for British Columbia and Alberta.

But Roslyn Levine, executive legal officer for the Superior Court, said in a statement that the court already transfers positions between regions under instruction from Chief Justice Heather Smith.

“The chief justice adjusts the complement in regions, from time to time, by transferring a judicial vacancy from one region to another when the need arises and can be accommodated,” Levine said.

Levine explained that the current judicial roster has its roots in the 1990 merger of the High Court of Justice and the District Court.

Although they circulated around the province, all of the High Court judges were based in the provincial capital and they all joined the Toronto region in the new Superior Court of Justice. There were and have since been efforts to adjust the spread.

“The number of judges in the central east region, centred in Newmarket, has more than doubled since the time of merger,” Levine said. “Similarly, the number of judges in the central west region, which is centred in Brampton, has doubled since that time.”

Regional population isn’t the only factor that impinges on decisions about where judges will sit, said Levine, who pointed out that the number of supernumerary judges varies depending on the region and can thereby artificially inflate the roster in some areas.

According to Levine, there’s a plan to boost the number of supernumerary judges in the central east region over the next three years that will add the equivalent of four full-time judges to the bench.

The number for Toronto is also boosted by the fact that four judges sit there daily as part of the Divisional Court. As the province’s financial centre, it also has a distinct commercial list served by six judges. In addition, it has a class action team with three more judges.

In any case, Levine said the court is limited by the availability of facilities to accommodate more judges.

During her speech at the opening of the courts ceremony this month, Smith highlighted several courthouses that are bursting at the seams under the stress of a packed criminal jury trial list.

In Brampton, things have “hit a wall,” she said, adding that the situation in Newmarket and Barrie was “dire.”

“To effectively address the challenge at these locations, our court’s first pressing requirement is securing the necessary court space to conduct all pending criminal jury trials,” Smith said.

For his part, Prutschi says getting trial dates in Brampton is “notoriously difficult.”

“Newmarket has had a major population explosion. It’s growing at an extremely rapid rate and Barrie is similar, so the courthouses just aren’t growing at the same rate as the population they serve.”

To see a map of how the judicial numbers stack up across Ontario,

click here.

While 91 judges are assigned to the court’s Toronto region to serve a population of almost 2.7 million, the central east region, which includes Barrie, Newmarket, and Oshawa, Ont., gets just 44 judges for a similar combined population.

While 91 judges are assigned to the court’s Toronto region to serve a population of almost 2.7 million, the central east region, which includes Barrie, Newmarket, and Oshawa, Ont., gets just 44 judges for a similar combined population. He says the difference between Toronto and surrounding communities is less acute in his area of practice, something he puts down to the nature of the work judges are doing in the provincial capital.

He says the difference between Toronto and surrounding communities is less acute in his area of practice, something he puts down to the nature of the work judges are doing in the provincial capital.