Lawyers who represent practitioners in discipline proceedings are deeply concerned about an increase in interim suspensions the Law Society of Upper Canada has brought in recent years.

When the law society feels that allegations against a lawyer are so serious that they could put the public at serious risk of potential harm, it can bring a notice of motion for what’s called an interlocutory suspension to the regulator’s tribunal. If successful, this stops a lawyer from practicing on an interim basis while an investigation and potential prosecution are being carried out.

In the first six months of 2017, the law society issued 19 interlocutory suspension motions, compared to 11 during the same period in 2016.

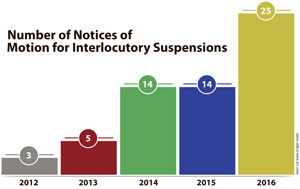

The law society brought 25 interlocutory suspension motions in all of 2016. This was an increase from the 14 that were brought in each of the two previous years. The law society issued only five in 2013 and three in 2012.

But the increase of such interim suspensions has raised alarm bells for lawyers who represent practitioners.

At the heart of their concern is whether the law society is properly considering the tension between an accused lawyer’s right to due process and that of its public image.

“There has been a bit of a tsunami of interlocutory suspension applications,” says William Trudell, a lawyer who represents practitioners in such proceedings.

Lawyers say interlocutory suspensions are draconian and have significant impact on practitioners, forcing them to close their practice during the duration of the order. When the law society is successful in bringing an interlocutory suspension, the allegations become public at the front end of an investigation.

The fact they are brought so early in the process makes them hard to defend as lawyers can often not know all the allegations they are facing, lawyers say.

The allegations could also be proven untrue or not be as serious as first thought.

Trudell says such suspensions can have devastating effects on a lawyer’s reputation, particularly in small communities.

“It’s very hard to get back on your feet unless you are in a large firm, where your chair might be kept warm,” he says.

“So that’s a real concern.”

He says if the law society is going to continue to use interlocutory suspensions, the tribunals are going to need to be very careful to make sure they are not just bowing to public pressure.

“I don’t think panels should be overwhelmed by a cloud when they’re deciding these issues because they are carrier ending in many respects,” Trudell says.

Compounding the issues that can arise from such suspensions, Trudell says, lawyers will often be self-represented in interlocutory suspension motion hearings.

Lawyers say they believe the law society’s increased use of interlocutory suspensions was prompted by media scrutiny and public pressure about how the regulator handled particular complaints against lawyers accused of exploiting vulnerable clients.

Some say the use of motions for interlocutory suspensions may be driven by tactical and economic reasons.

Richard Watson, a lawyer who represents accused practitioners, says such motions are brought on very short notice and create a “somewhat prejudicial super-charged” atmosphere while leaving the accused lawyer with little time to put together a defence.

“While an interlocutory suspension is in principle merely a prelude to a full conduct application, the practical effect of a successful motion for an interlocutory suspension is that of a pre-emptive strike from which the licensee never recovers,” he says.

Bencher William McDowell, who is chairman of the law society’s Professional Regulation Committee, says the rise in interlocutory suspension motions can be attributed to a reorganization of the way the regulator investigates complaints. The change meant discipline counsel became involved much earlier in the process, with a view to see whether a suspension was necessary.

“This is simply the outcome of having legal analysis earlier in these cases. This isn’t a kneejerk response to media focus on the issue,” McDowell says.

“It isn’t a new attitude at the law society. It’s simply that we now have lawyers looking at these cases as they come in the door and this frankly isn’t a surprising outcome.”

David Sterns, the outgoing president of the Ontario Bar Association, says he thinks the law society is going in the right direction with the increase of interlocutory suspensions.

Sterns has pushed in the past for the law society to be more transparent early on in the disciplinary process in serious cases.

“In those cases of potential serious impropriety, particularly financial impropriety, the law society has to act quickly. It has to put its resources on it and it has to act in the public interest and when appropriate, has to also let the public know about the allegations that it’s sitting on,” he says.

Sterns says using more interlocutory suspensions means that the public will be protected while an investigation is going on and it also allows lawyers to make their case as to why there should not be a suspension.

“In terms of the increase in suspension applications, I think that’s a good thing for the public, and in the greater scheme of things, it’s a good thing for the profession,” he says.

Those who defend accused lawyers are not the only ones who have raised concerns over the potential impact of interlocutory suspensions on practitioners.

In 2016, the law society’s division hearing panel granted an interlocutory suspension in

Law Society of Upper Canada v. Ejidike, but it also expressed concern over how it might affect the accused. Bencher Malcolm Mercer, chairman of the three-member panel, noted that the ensuing investigation could take six to eight months and the whole process might last as long as 18 months.

In the decision, Mercer said that while many suspension orders will be seen as the correct choice in retrospect, some will not, and an increasing number of lawyers are at risk of “paying this necessary price.”

“While vigilant public protection is necessary, it is important to ensure that the conduct of licensees under interlocutory suspension is indeed promptly investigated, and where appropriate, prosecuted,” Mercer wrote in the decision. “As well, there is value in better assuring during a suspension that the suspension continues to be in the interests of justice. Fair assessment of the impugned conduct may change over time.”

He also pointed out that the law society has limited investigative resources and that an increase in interlocutory suspensions “no doubt additionally burdens investigative resources.”

Mercer said that there should be a better way to address certain situations where suspensions should not continue. The panel set out a template that would allow the accused lawyer to submit a motion after five months, requiring the law society to prove that the suspension should continue.

Mercer declined to be interviewed.

Trudell says that interlocutory suspensions offer little protections to lawyers. Going forward, he says, the law society needs to understand it has a duty to lawyers and to make sure there are some built-in protections if the regulator is going to follow the recent trend of using interlocutory suspensions more frequently.

McDowell says that the increase in suspensions in recent years is not a spike and will likely be the level of such motions going forward, as the law society looks to protect the public.

“There’s no question that an interlocutory suspension has a huge impact on the way a lawyer’s professional life unfolds, but sometimes regrettably it’s necessary to do that to protect the public,” McDowell says.

Hear more about this topic in our video,

Law Society of Upper Canada expands use of interim suspensions.

To read the first story in the summer series in

Law Times focusing on lawyer discipline, you can read

Law Society of Upper Canada looks to tackle complaint delays.

When the law society feels that allegations against a lawyer are so serious that they could put the public at serious risk of potential harm, it can bring a notice of motion for what’s called an interlocutory suspension to the regulator’s tribunal. If successful, this stops a lawyer from practicing on an interim basis while an investigation and potential prosecution are being carried out.

When the law society feels that allegations against a lawyer are so serious that they could put the public at serious risk of potential harm, it can bring a notice of motion for what’s called an interlocutory suspension to the regulator’s tribunal. If successful, this stops a lawyer from practicing on an interim basis while an investigation and potential prosecution are being carried out.  At the heart of their concern is whether the law society is properly considering the tension between an accused lawyer’s right to due process and that of its public image.

At the heart of their concern is whether the law society is properly considering the tension between an accused lawyer’s right to due process and that of its public image.  Sterns has pushed in the past for the law society to be more transparent early on in the disciplinary process in serious cases.

Sterns has pushed in the past for the law society to be more transparent early on in the disciplinary process in serious cases.