In the last two decades, William Malamas has sued dozens of parties, many of them lawyers, in numerous actions.

Now, as he appeals a Superior Court judge’s order declaring him a vexatious litigant, the former real estate developer says the justice system has failed him.

Now, as he appeals a Superior Court judge’s order declaring him a vexatious litigant, the former real estate developer says the justice system has failed him.

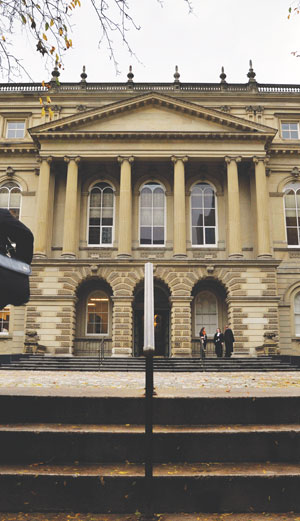

“The system has failed me miserably,” he says as he sits outside the Ontario Court of Appeal following arguments last week challenging a June 2012 decision barring him from bringing any more applications.

He lugs a box carrying several thick binders that include his affidavits. During the June 11 hearing, appeal court Justice John Laskin made a remark about the length of Malamas’ claim but assured him that the court had read it all.

In the last 20 years, the now self-represented litigant has spent more than $1 million in legal costs, he tells Law Times. “In the end, I couldn’t keep it up. That’s why now I’m doing this alone.”

Malamas’ long legal saga began some time in the early 1980s when he was the landlord of a Danforth Avenue property in Toronto that had the National Bank of Greece as its tenant. He would later lose his property when the recession hit and his mortgage exceeded the value of the property.

In his developer days, Malamas got into a dispute with the occupant bank and sued it for rent arrears and damages for breach of the lease.

In the coming years, he sued virtually all of the lawyers who represented him in that litigation and other cases he came to be involved in. According to court documents, Malamas argues the lawyers “developed an attitude of increasing malice” toward him during their representation of him.

The law firms named in various lawsuits over the years, some of which no longer exist, include McCarthy Tétrault LLP, Toome Laar & Bell, Raphael Professional Corp., Goodman and Carr LLP, Gardiner Roberts LLP, and Hodder Solicitors, according to a ruling last year in Teplitsky Colson LLP v. William Malamas.

The June 2012 court decision that declared Malamas a vexatious litigant notes he sued a total of 16 lawyers over a span of six years. That number doesn’t include the lawyers who were once the owners of a building adjacent to his Danforth Avenue property.

The Stanoulises and DiBiases, some of whom are lawyers, accused Malamas of encroaching on their property through new construction in the area. Malamas has since maintained an acrimonious relationship with the family.

To this day, Malamas believes lawyers are tapping his phones and hacking his e-mail.

Nick, Donna, Christina, Gary, and Thomas Stanoulis are five of the 26 parties who filed an application to have Malamas declared a vexatious litigant. The total damages Malamas sought from all 26 parties exceeded $300 million.

According to Superior Court Justice Frank Newbould, who barred Malamas from bringing any further applications, his allegations of fraud against all of the lawyers he has sued are based on no evidence. Newbould also found Malamas “has caused an inordinate amount of time to be spent in the court process.”

“In nearly every action commenced by Mr. Malamas over the last 20 years, he has claimed that each of the defendants in each of the proceedings were the direct cause of his personal and financial ruin,” Newbould wrote in Teplitsky Colson last year.

At times, judges have been rather blunt in their opinions of Malamas. “Mr. Malamas’ behaviour is quite extraordinary, to the extent that one suspects he would benefit from a visit to a psychiatrist,” one judge said in 1995 after Malamas was charged with assaulting the Stanoulises.

For Malamas, his cases are “controversial” because he’s bringing actions against lawyers who he believes are trying to cover up their misconduct by “throwing [him] out of court” through a vexatious litigant declaration.

In court last week, Malamas spoke of what he later described as one more “dishonesty” by the lawyers involved. The counsel who wrote the affidavit to declare him a vexatious litigant, William O’Hara, had no authority to write it on behalf of all 26 parties, Malamas argued.

His main argument, he says, was that O’Hara didn’t have instructions from all 26 parties, which include corporations, to write the affidavit.

Had O’Hara obtained instructions, he would have produced a resolution by the board of directors from the corporate applicants, according to Malamas, who suggests that didn’t happen.

Malamas digs into the box carrying his affidavits and fetches a piece of paper outlining the rules of representation by a solicitor.

They state: “If the lawyer has commenced a proceeding without the authority of his or her client, the court may, on motion, stay or dismiss the proceeding and order the lawyer to pay the costs of the proceeding.”

Ray Thapar, one of the lawyers representing the parties who brought the vexatious litigant application, says he first started doing work on the case as an articling student 13 years ago.

His office has many boxes full of documents relating to the Malamas case, he adds wearily. He describes the decades-long legal drama as being the result of “an overwhelming obsession with conspiracy.”

As to Malamas’ latest appeal, the affidavit O’Hara wrote relied on established facts, such as the number of actions Malamas brought and the decisions that followed, Thapar notes.

“There was really nothing contentious in the affidavit. It wasn’t hearsay.

It was all information that was in the written decisions, ” he adds, noting that particular procedural step doesn’t have a huge impact.

But for Malamas, it makes all the difference. “The lawyers are abusing the court process,” he says.

“They don’t respect the rules of their profession. They take advantage of being officers of the court.”

The appeal court has reserved its decision in the case. Both parties have made cost submissions in the $30,000-$40,000 range.

Update: Man’s appeal of vexatious litigant finding dismissed