Despite being late to the game, Canadian courts are ready to start trending on Twitter, according to a group of judges and other legal experts who have proposed new national guidelines for the use of social media in court.

The group representing the Canadian Centre for Court Technology proposed recommendations in late October that would allow anyone attending an open Canadian court to tweet away during the proceedings unless specifically prohibited by the judicial officer.

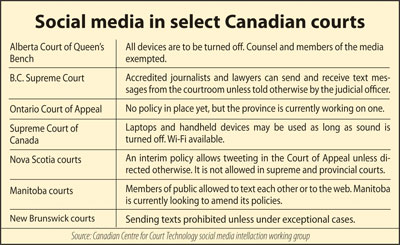

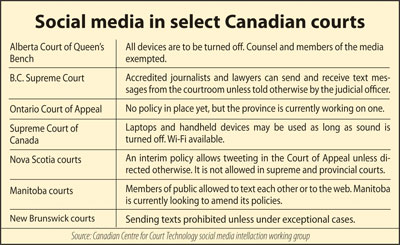

“In the last two years, the issue has been coming up in different courts and there has been no consistent response,” says Ontario Superior Court Justice Frances Kiteley, co-chairwoman of the centre’s board of directors.

Kiteley says the permissive guidelines follow a nationwide survey that found that judges, defence lawyers, Crown prosecutors, journalists, and court administrators were leaning toward a policy of allowing the use of social media in the courts.

Ontario doesn’t have a policy on live tweeting from courts, but there is one in the works.

Some provinces allow the use of social media by default unless a judge restricts it while others prohibit its use except in cases where a judge permits it. In B.C. courts, only accredited journalists and counsel can use cellular devices.

“More and more Canadians are getting their information and information on the courts from social media,” says Stephen Bindman, one of the members of the centre’s group that drafted the guidelines.

The guidelines take into consideration the blurring boundaries between accredited journalists and the general public, says Bindman.

But everyone publishing online via tweets or blogs should bear the responsibility of abiding by publication bans, the guidelines say. The draft also recommends banning jurors from using all electronic devices.

Independent media lawyer Daniel Henry, who has pushed for audiovisual access in courtrooms, says social media is an important tool of communication.

“Public confidence in the system comes from access to the system. It’s time, frankly, that in this day and age the justice system provides that kind of access,” he says, calling the guidelines “a certainly welcome step.”

Detecting breaches of publication bans and other restrictions may be tricky with social media, says Henry, but it’s all the more reason why judges should consider “both the necessity and practicality of publication bans.”

New rules on social media may mean judges will have to brush up on their social media skills in order to understand what exactly is involved, something Kiteley says the National Judicial Institute is “very alert” about.

Some provinces deem tweeting acceptable in appellate courts but not in trial courts where there’s a risk of influencing the jury.

Kiteley recalls the case of former RCMP officer Kevin Gregson, who was convicted this year in the first-degree murder of Ottawa police officer Eric Czapnik. At one point during the trial, a reporter tweeted before the jury entered the courtroom that Gregson had arrived in shackles, something the courts don’t want jurors to see.

“The reality is, though, that can happen now [through traditional media],” says Kiteley, who adds that the risks of compromising proceedings are greater with the use of social media.

“We should be able to manage those risks,” she says. She suggest having more announcements in courts and signs to remind the public and journalists what they can’t publish on social media or elsewhere.

Bindman, a former journalist with years of experience covering the courts, has concerns of his own about reporters tweeting from the courtroom.

“I wonder if Twitter is turning journalists into stenographers,” he says.

“If journalists are tweeting, are they taking notes?”

Context, analysis, and editing can go out the window while blogging live, but these are issues journalists, and not the courts, should consider, says Bindman.

Although journalists could use electronic devices at the Michael Rafferty trial, some media outlets decided not to tweet during the proceedings due to the graphic nature of the materials.

“That’s the kind of journalistic consideration I encourage,” says Bindman.

The other risk, according to Jean-François De Rico, a partner at Langlois Kronström Desjardins LLP who participated in a forum on social media last month, is that more access could in some cases result in precisely the opposite of what it intends to achieve. The immediate release of witnesses’ information to the public may create “a chilling effect,” he says, noting that could ironically make the courts a more guarded space.

For more, see "Court says no to live tweets at trial."

The group representing the Canadian Centre for Court Technology proposed recommendations in late October that would allow anyone attending an open Canadian court to tweet away during the proceedings unless specifically prohibited by the judicial officer.

The group representing the Canadian Centre for Court Technology proposed recommendations in late October that would allow anyone attending an open Canadian court to tweet away during the proceedings unless specifically prohibited by the judicial officer.