Lawyers say a recent Divisional Court decision will reinforce shareholders’ rights to call special meetings.

In

Koh v. Ellipsiz Communications Ltd., the court overturned an application judge’s decision to grant an exception to the board of directors of a company, which would have stopped a shareholder from requisitioning a meeting. The court found that in order to provide this exception, the board of directors must clearly prove that enforcing a personal claim or grievance was the primary purpose of the requisition.

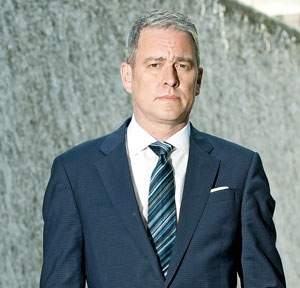

“It affirms the basic principles of a shareholder democracy,” Geoff Moysa, the lawyer who represented the shareholder, says of the decision.

“It’s the shareholders that ultimately own the company and will make these decisions.”

Lawyers say the decision sets a high threshold that directors must meet to receive the exception, making it harder for them to decline a requisition request based on the personal grievance exception.

The decision was also the first by an appellate court to acknowledge the right of shareholders to requisition a meeting as a “fundamental right,” lawyers say.

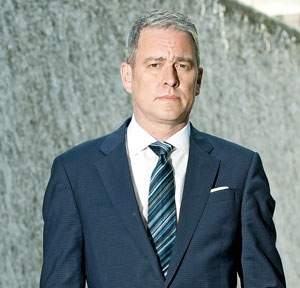

Derek Bell, a partner with DLA Piper (Canada), who was not involved in the case, says the decision reflects a concern about board entrenchment and how directors may use a part of the Ontario Business Corporations Act, known as the personal grievance exception, to prevent shareholders from removing them.

Under the act, all shareholders who hold at least five per cent of the company’s stock have a right to requisition the board of directors to call a meeting unless one of three exceptions applies. One of those exceptions is when it “clearly appears that the primary purpose of the proposal is to enforce a personal claim or redress a personal grievance against the corporation or its directors, officers or security holders.”

Bell says that directors could adopt a loose interpretation of the exception in order to stifle shareholders meetings that could oust them.

“The real concern about this exception to the statute is that a board who wants to keep their job could employ a pretty liberal definition of this exception and say, ‘Oh, well, sorry you’re not going to be able to decapitate us this week because we think that you’re advancing a personal grievance,’” Bell says. “And, really, what the appeal court has done here is bat that down.”

But the Divisional Court decision shows the personal grievance exception will not be an “easy catch-all” for denying a requisition request, he says.

The dispute arose when a shareholder, Tat Lee Koh, who holds around 42 per cent of the company’s shares, requisitioned a meeting to consider removing newly elected directors.

The company became publicly traded in 2015, and it held a first annual general meeting in 2016, in which a slate of directors was elected, including a group referred to in the decision as the “Canadian Directors.”

Koh opposed this election and demanded the Canadian Directors resign. Otherwise, he said, he would requisition a shareholders’ meeting to remove them.

When they did not resign, Koh submitted the requisition and the board declined it, saying it was for the primary purpose of redressing a personal grievance against the company. The board claimed that Koh’s personal grievances included that he wanted to be chairman of the company among a number of other complaints.

The case turned on whether Koh had requisitioned the meeting because of a personal claim or personal grievance.

The court found that the board of directors had failed to establish that the primary purpose of the requisition was to redress a personal grievance against them, and that if the directors and the shareholder disagree on the direction of the company, the shareholders should be allowed to decide those issues.

“On fair review of the record, it appears that the appellant and the Canadian Directors have a significant difference of opinion as to the course that the company should take, and how it should be managed,” Justice Ian Nordheimer wrote in the decision.

“It seems to be that the shareholders ought to be permitted to decide those issues.”

Nordheimer also said it is not “sufficient to show simply that the shareholder requisitioning the meeting has an element of personal interest in the matter.

“That would cast the scope of the personal grievance exception too broadly.”

Moysa says the decision confirms that the exceptions to a shareholder’s fundamental right to call a meeting should be construed narrowly. He says the decision ultimately puts the onus on directors to prove that a shareholder is acting out of a personal grievance.

Moysa says the decision also affirms the court’s role in corporate disputes.

“The role of the court is one of a referee to these disputes rather than being the forum that determines the dispute itself,” says Moysa, who is a partner with McMillan LLP.

“The court is there to essentially determine whether or not the shareholder has that right . . . but, ultimately, it will be up to shareholders in a proxy fight or in a meeting of shareholders to determine the actual business matters and issues.”

The court also determined that while Koh had expressed his concerns to board directors in “personal terms” he had a valid difference of opinion as to the business steps that should be taken by the company.

Jim Blake, a corporate lawyer, who was not involved in the case, says historically the courts have deferred to the business judgment sense of a board of directors under the business judgment rule. The rule holds that directors are in a better position than the courts to make decisions concerning their company.

“This is a bit of a breakthrough. It changes it from business judgment rule in the case of a requisition meeting to saying unless the board can prove this is truly a personal claim then the meeting must be held,” says Blake, a partner with McLean & Kerr LLP.

“It’s a little bit of a shifting of power in favour of existing shareholders and their ability to requisition a shareholders meeting.”

Jay Naster, the lawyer representing the respondent, said he was not in a position to comment.

In Koh v. Ellipsiz Communications Ltd., the court overturned an application judge’s decision to grant an exception to the board of directors of a company, which would have stopped a shareholder from requisitioning a meeting. The court found that in order to provide this exception, the board of directors must clearly prove that enforcing a personal claim or grievance was the primary purpose of the requisition.

In Koh v. Ellipsiz Communications Ltd., the court overturned an application judge’s decision to grant an exception to the board of directors of a company, which would have stopped a shareholder from requisitioning a meeting. The court found that in order to provide this exception, the board of directors must clearly prove that enforcing a personal claim or grievance was the primary purpose of the requisition.