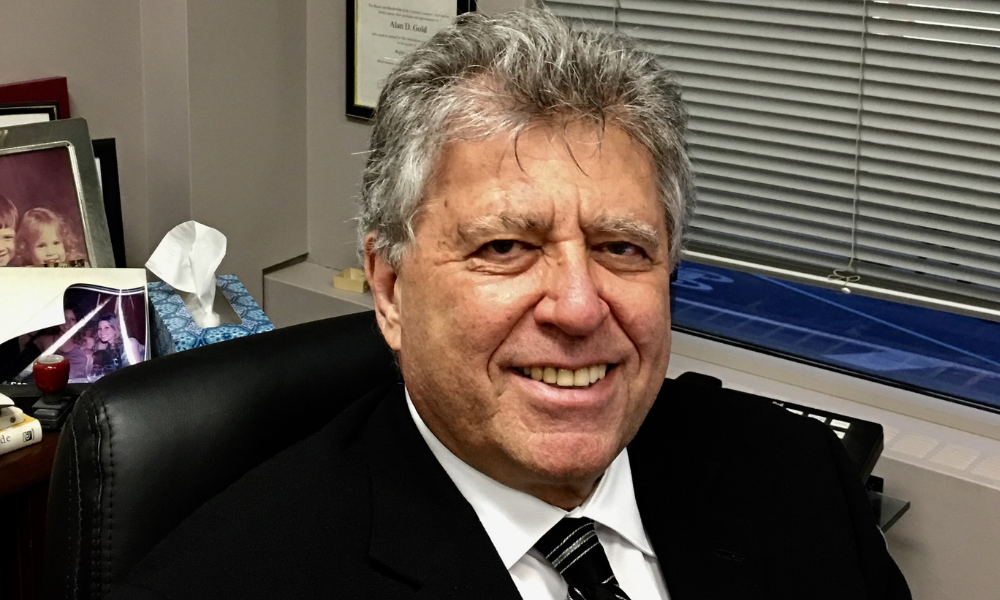

Pole cameras represent significant s. 8 issue, says Alan Gold, who plans to appeal to SCC

The Court of Appeal for Ontario has confirmed that erecting a pole with a camera attached on public property to surveil the front of a drug-trafficking suspect’s home was constitutional because the suspect had no reasonable expectation of privacy.

In R. v. Hoang, 2024 ONCA 361, the court held that using the pole camera was not a search under s. 8 of the Charter, which protects against unreasonable search or seizure. While dismissing the conviction appeal, the court allowed the appeal on the 18-year sentence imposed, finding that the trial judge failed to apply the principle of restraint.

Alan Gold, who acted for the appellant, says the question of pole cameras’ constitutionality is currently the most important s. 8 issue.

“It has generated numerous American cases – going both ways – and may soon reach the United States Supreme Court.”

Gold has proposed to seek leave to the Supreme Court of Canada on the s. 8 issue.

In the decision, the court cited the summary of the law on s. 8 in R. v. Bykovets, 2024 SCC. The claimant arguing for a s. 8 breach must show that an unreasonable search and seizure occurred. There is a search where “the state invades a reasonable expectation of privacy.” An expectation of privacy is reasonable where “the public’s interest in being left alone by the government outweighs the government’s interest in intruding on the individual’s privacy to advance its goals.” Courts will analyze an expectation of privacy by examining the subject matter of the search, the claimant’s interest in the subject matter, their subjective expectation of privacy, and the reasonableness of that subjective expectation.

Justice Lorne Sossin, writing the reasons for the Court of Appeal’s panel, said there was no question the appellant had a subjective expectation of privacy. The question was whether his expectation was objectively reasonable.

The pole camera was pointed at the appellant’s house and monitored and recorded everyone who came and went for eight days. One evening, the camera captured a man exiting his vehicle carrying a duffel bag, which appeared to be heavy. He entered the appellant’s garage and was carrying a small plastic bag when he returned to his car. Later, the camera captured the appellant carrying the duffel bag out of the garage and placing it in one of his cars. The police also surveilled the appellant in person and saw him moving various items and bags between his vehicles.

Following this activity, the police executed warrants to enter and search one of the appellant’s cars covertly. There, they discovered a knapsack with cash, a shotgun and magazine with two shells, a bag containing a cutting agent, a large volume of narcotics, and more money. The police seized the vehicle, obtained further warrants, and located a trap compartment holding more narcotics.

The application judge had found that, while the recordings were made secretly, the camera was on public property, did not record audio, and captured activity at the front of the house that was “visible to the public eye.”

The application judge applied the factors from R. v. Tessling, 2004 SCC 67. The appellant did not argue that the judge erred in applying those factors. He argued that technological advances such as pole cameras should induce an evolution in the approach to the expectation of privacy.

Gold says the Court of Appeal accepted the trial judge’s reasoning, based on Tessling, that the pole camera evidence did not raise a s. 8 issue. The “clear and important issue of law” for the SCC appeal will be that “Tessling is not an exhaustive checklist in relation to s. 8 and does not apply to new and different s. 8 contexts.”

“As the police use new technologies to observe and record citizen activities, the Tessling factors, derived from one particular context, may have no, or limited, application to new police surveillance activities,” says Gold. “This case provides the perfect fact situation for the SCC to enunciate the appropriate s. 8 principles applicable to pole cameras and other automated state surveillance and recording techniques, state activities that have become ubiquitous in the modern digital world.”

“A pole camera has a Big Brother undertone to it,” the appellant’s factum states. “Undertone that becomes the very melody when you consider the contemporary availability of ubiquitous wireless networks and increased availability of miniature devices at nominal costs as well as the massive digital storage media now available.”

The appellant argued that modern technology allows entire cities to be continuously recorded, with the state tracking “unlimited amounts of information about what its citizens are up to.” While the camera recorded what was publicly visible, he argued he had the “right to be left alone.”

The appellant referred to US jurisprudence recognizing that long-term pole-camera use was unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unlawful search and seizure.

In different circumstances, Sossin said, pole camera surveillance could capture material that would give rise to a reasonable expectation of privacy, depending on the duration, scope, nature of the surveillance or “other contextual or technological factors.” But in this case’s circumstances, the camera was in a public space and only captured what a police investigator could have seen “without any additional capture of sound or close-up camera angles, and for a limited period of time,” he said.