Migrant workers' colour and place of origin were factors in the DNA canvass, tribunal said

The Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario found that the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) violated the Human Rights Code when it collected DNA samples from dozens of migrant farmworkers during a sexual assault investigation in 2013.

In Logan v. Ontario (Solicitor General), 2022 HRTO 1004, the applicant was a Black man from Jamaica. A farmer in Elgin County, Ontario, employed him, and he lived with other migrant farmworkers in one of several bunkhouses spread out on the farm property.

In October 2013, a woman was sexually assaulted in her home. She lived alone in an isolated area near the farm where the applicant worked. In her police statement, she described the assailant as a male migrant worker who was Black, in his mid-to-late 20s, between five feet 10 inches and six feet tall, muscular, and with a very low and raspy voice with a heavy accent.

Detective Superintendent Gonneau then met with Detective Staff Sergeant Raffay and the supervising sergeant, and all agreed that a voluntary DNA canvass was an appropriate investigative tool. They decided to interview and seek consent to take DNA samples of all migrant workers in nearby farms.

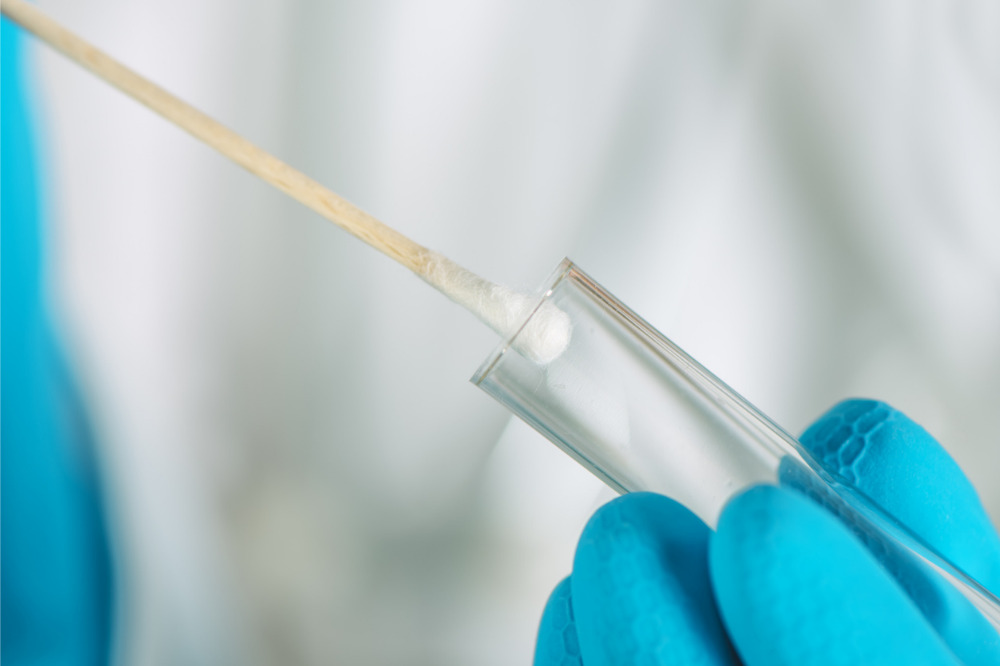

The OPP organized the DNA canvass of the migrant workers through the farm owners and conducted it on five farm properties. The applicant claimed that he did not want to provide a sample of his DNA but agreed to do so to appease the police and his employer. In total, the OPP collected approximately 96 DNA samples.

The OPP submitted the DNA samples to the Centre for Forensic Analysis (CFS) for analysis and the vaginal swab from the sexual assault kit. The CFS informed the OPP that none of the DNA samples collected from the migrant workers matched the crime scene DNA profile.

In his application with the HRTO, the applicant alleged that the sexual assault investigation in 2013 was discriminatory because of his race, colour, and place of origin, contrary to the Human Rights Code. Specifically, he alleged that these grounds were a factor in the request made by OPP for a voluntary DNA sample from him and other migrant farmworkers.

The OPP denied discrimination and argued that the DNA canvass was based on the description of the assailant as a migrant farmworker, the proximity of migrant farmworkers to the scene of the crime, the urgency of the situation, and the voluntariness of the DNA request.

In granting the application, the HRTO found that race, colour, and place of origin were factors in the DNA canvass. The applicant had therefore established discrimination contrary to the Human Rights Code.

According to the HRTO, there was direct evidence from the police officers that the OPP conducted the DNA canvass on the applicant and other migrant farmworkers based on their race, colour and place of origin. For instance, Raffay testified that one of the factors in the decision to ask migrant farmworkers for their DNA samples was the “colour of their skin.” Moreover, the police did not conduct the DNA canvass on White farm owners or any other males in the community.

“The evidence is that the victim of the sexual assault had described the assailant as a Black male with a heavy accent which she thought was Jamaican, and she believed he was a migrant worker. This description of the suspect is based on these Code grounds: race, colour, and place of origin,” Adjudicator Marla Burstyn wrote. “The police relied on this information as the basis for the DNA canvass.”

The HRTO also found that although the police officers interviewed the migrant farmworkers and learned that some of them did not reasonably match the description provided by the victim, they still asked for DNA samples. Likewise, the OPP requested DNA samples even if some workers, including the applicant, provided alibis.

“This evidence shows that the police officers failed to reassess the scope of the DNA canvass based on new information obtained during the interviews they conducted with migrant workers,” Burstyn wrote. “Past tribunal decisions have found that disregard of information to the contrary and failure to reassess policing steps is an indication of discriminatory conduct.”

The HRTO also relied on the Ontario Human Rights Commission’s (OHRC) “Policy on Eliminating Racial Profiling in Law Enforcement” to determine if the applicant had established a prima facie case of discrimination. The policy indicates that an individual’s race can form part of a criminal profile to hone in on possible suspects, depending on how the investigation relies on race.

The policy also states that racial profiling can happen when law enforcement disregard a specific suspect description in favour of investigating someone whose only matching characteristic is their race, skin colour, or ancestry. Therefore, care should be taken when officers use “sweeps” to scrutinize groups of racialized individuals when they could use a more precise approach based on the information available.

“In this case, the OPP selected the migrant workers for investigation by relying on race and related Code grounds because of the victim’s description that the suspect was a migrant worker in the area,” Burstyn wrote. “The OPP disregarded additional physical descriptions provided by the victim.”

The HRTO said that the OPP cast “a wide net” by conducting a DNA canvass on all migrant farmworkers based on their race, colour and place of origin, even if they did not reasonably match the height range, age range, build, and lack of facial hair described by the victim.

“Without making a specific finding, I note for the purposes of this prima facie case analysis, that the failure to act on the other physical descriptors of the suspect, in favour of race and related Code grounds, raises concerns of racial profiling under the OHRC policy,” Burstyn wrote. “In conclusion, I find that this evidence establishes a prima facie case of discrimination on the basis of race, colour and place or origin.”