He pushed the Financial Services Regulatory Authority to fix the catastrophic impairment guideline

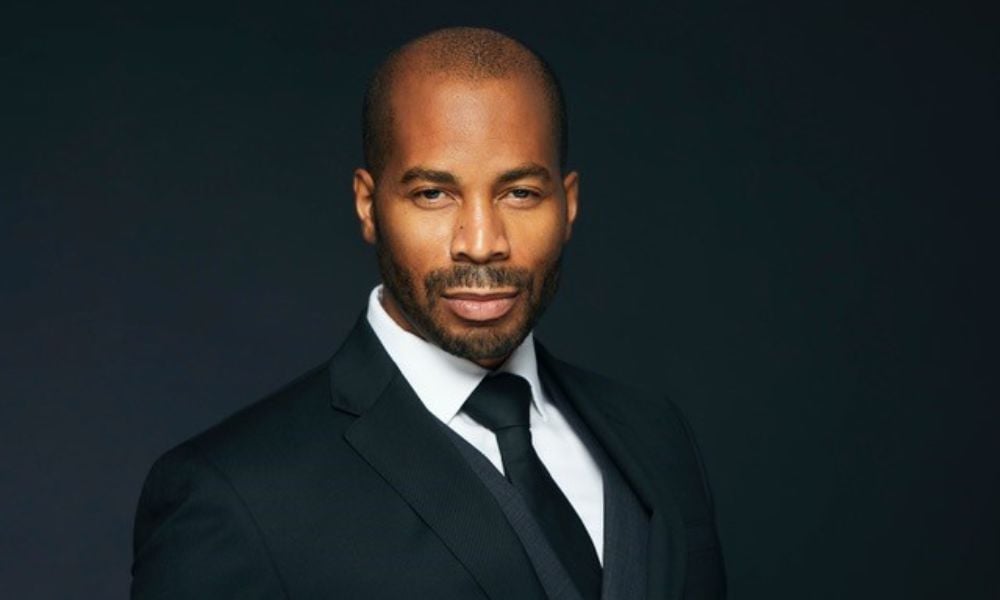

Andrew Rudder’s battle is a story about what fighting for your client really means.

It’s tempting to say that Rudder of Rudder Law Professional Corporation, a personal injury boutique in Burlington, Ontario, is the story’s focal point.

But Rudder would disagree. The focal point, he would insist, is his client, a 17-year-old Indigenous single mother of a severely disabled son. She was catastrophically injured in a car accident on the Six Nations Reserve in Hagersville.

Like many unknown others before her and – but for Rudder – many to follow, she could not access the compensation she deserved because of an obscure bureaucratic glitch that – to date at least – no one can explain.

Rudder’s client, who wishes to remain anonymous, was the only passenger in her cousin’s car in July 2018. The vehicle went off the road into a ditch, rolling several times. The cousin was uninjured; the client was not.

An ambulance took her to Brantford General Hospital, where doctors quickly realized that she had a catastrophic spinal cord and head injuries that required a transfer to Hamilton General Hospital, one of the hospitals comprising the Hamilton Health Sciences network.

X-Rays at HGH confirmed “intracranial pathology,” or internal damage and bleeding in the skull and brain.

The Regional Rehabilitation Centre, also part of HHS, normally deals with brain trauma. But the attending physicians at HGH determined that injuries to the teen’s elbow, hand and spine took priority. They admitted her for treatment by orthopedic surgeons at HGH’s Surgical Trauma Centre.

When Rudder took his client’s case to the insurer, Desjardins, the company refused to recognize the teen as suffering from catastrophic impairment under the Statutory Accident Benefits Schedule. They declined because she had not been admitted to one of 12 public hospitals included in the 2016 Catastrophic-Impairment Public Hospitals Guideline issued by the Financial Services Commission of Ontario, the predecessor to the Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Ontario.

While the guideline listed the Regional Rehabilitation Centre at HHS as a hospital that meets the criteria for determining whether an individual under 18 has a “traumatic brain injury,” HGH was not on the list even though it was a “Level 1” trauma centre.

“Because the surgeons decided to admit my client to the Surgical Trauma Centre at HGH to deal with her limb and spine injuries, my client fell in the cracks,” Rudder says.

Rudder dug in. He took a deep dive into the evolution of the catastrophic impairment designation.

“I discovered that the Ministry of Health designates lead trauma hospitals, and HHS generally was on that list,” he says. “I also interviewed members of the expert medical panel that the Ministry of Finance had consulted when it did a review that included the superintendent’s report on catastrophic impairment in SABS.”

Rudder discovered that the panel had recommended that patient admission to a Level 1 trauma centre was enough to satisfy the “catastrophic impairment” designation.

“Somehow, FSCO lost sight of that when they drafted the guideline, even though HHS was on the MOH list as a Level 1 trauma centre,” Rudder says.

Confronted with Rudder’s research, Desjardins changed course and granted his client the “catastrophic impairment” designation.

“The case settled for close to $1 million, which was the policy limit,” Rudder says.

But Rudder couldn’t stop thinking about it.

“I kept wondering how many other children were or would be affected by this bureaucratic glitch,” Rudder says.

So he took his research to FSRAO. His work with Ann MacKenzie, senior manager of policy interpretation – auto/insurance productions at FSRAO, produced an amended guideline in October 2020 that recognized admission to any “lead trauma,” or Level 1, facility as satisfying the “catastrophic impairment” criteria.

Still, Rudder wasn’t satisfied.

“Because most Level 1 trauma hospitals are in major centres, I came to see the issue as involving discrimination based on geography. The difficulty is that the net is not wide enough because it means that if an injured person is admitted to a Level 2 centre that can handle trauma, like in Kingston, they won’t qualify as catastrophically impaired. That’s even truer in more remote districts where we find the Level 3s.”

Even as Rudder continues to press for further change, he was recognized for his efforts: earlier this week, and against international competition, he won the 2022 Reisman Award for the best new law firm.