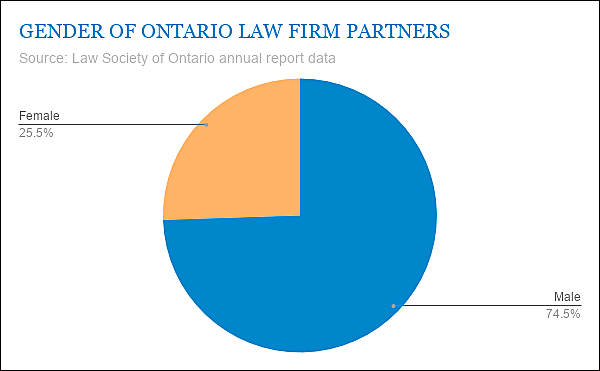

Men continue to be more likely than women to be partners at law firms, 2018 statistics from the Law Society of Ontario show.

_web.jpg)

Men continue to be more likely than women to be partners at law firms, 2018 statistics from the Law Society of Ontario show.

The numbers show that Ontario has made little progress over the past few years in achieving gender parity at the partner level.

The statistics, released as part of the LSO’s 2018 annual report, show that about 12.4 per cent of lawyers in Ontario were male law firm partners, compared to only 4.3 per cent of lawyers who were female partners. That means that, of 41,576 lawyers in Ontario, 5,168 were male partners out of the 23,594 male lawyers. Of 17,982 women lawyers, 1,770 were partners.

In 2017, 12.9 per cent, or 5,206, of Ontario lawyers were male partners and 4.2 per cent, or 1,715, were female partners. In 2016, 13.4 per cent were male partners and 4.3 per cent were female partners.

The gap continues to be much smaller at the associate level. In 2016, 8.8 per cent of Ontario lawyers were female associates and 9.8 per cent were male associates. Two years later, 9.2 per cent of lawyers are female associates and 10 per cent are male associates.

It has been more than a decade since the law society launched its Justicia project in November 2008 to retain more women in private practice in Ontario. The project was launched after a May 2008 report said that women are more likely than men to leave their firms before joining the partnership. By 2014, 57 firms signed on to the project, and large law firms reported that retention had increased.

But as of last year, women are still more likely to work in government, while men are more likely to be sole practitioners, the law society’s new report shows.

Ontario Bar Association president Lynne Vicars says it’s good to see a balance of men and women in in-house positions and that it’s not a bad thing that women lawyers gravitate toward government. But the stark difference in partnership is troubling, she says, and indicates that the profession is “stuck.”

Vicars launched “solution circles” around gender equity as part of her mandate at the bar association, where small focus groups have targeted specific problems around advancing women in leadership in Ontario. The discussions have focused on issues such as childcare challenges and unconscious bias and have led to a list of resources on the OBA website. The OBA is looking for more firms interested in hosting the discussions.

_web.png)

“The goal is to produce tangible, small steps, not giant leaps that are going to take years to accomplish, but small steps that root out causes of inequality that we can take on immediately,” says Vicars. “This isn’t new. This is something that’s been looked at for decades now. That’s why we’ve tried to come up with different ways of finding small steps that can be taken rather than tackling everything at once.”

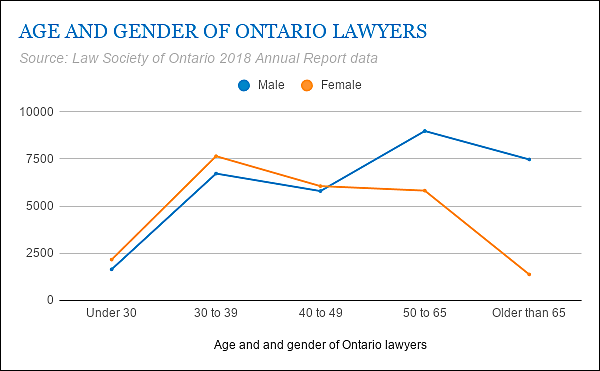

Women outnumber men in the profession until they reach their forties — but there are more men than women lawyers over age 50, the LSO’s 2018 report said. Nearly 17 per cent of Ontario lawyers are men over 50, and nearly 14 per cent are men over age 65. The share of lawyers that are women over 50 is almost 11 per cent, while the share of women over 65 is 2.6 per cent. For lawyers under 30, there are many more women than men.

Vicars says she would like to see more details on whether women continue to practise actively over that time.

“I think [the data set] makes things not look as bad as they are,” she says.

The LSO’s report did not go into detail on the racial identity of licensees, but it did say that almost 23 per cent of lawyers in the licensing process were racialized while 1.56 per cent were Indigenous.

In the last half of 2018, 61 per cent of complaints to the law society’s Discrimination and Harassment Counsel were made by women, a Feb. 28 report to Convocation said.

Naiyna Sharma, a counsel at Justice Canada and a founder of the South Asian Women in the Law Mentoring Program, says she created the mentoring program in part because she saw a missing link for women, particularly racialized women, looking to advance in the profession.

“I was working on a panel and a mentorship event. . . . There were a number of women around the table and no one could come up with a person from an equity [seeking] group to be at these events. I wanted someone in a middle-management position,” says Sharma. “They existed but no one knew them. I myself didn’t know about them. I realized we give so much lip service to wanting to do intersectional work, but that work is difficult if you don’t know who is out there. . . . [A] few choice individuals are selected for feedback.”

Sharma says that if women are only exposed to the superstar, exception-to-the-rule lawyers, female lawyers may internalize that it’s not a path that’s realistic for them, especially if they don’t come from a similar background.

“It makes a big difference for them to be able to connect with someone who has gone through it,” she says. “If I have a big dream like being on Bay Street or making partner, I can do it, because here is someone who has done it as well.

"Mentorship, outside of offering support, can plant the seed but also tell you the steps to water it, grow it and sustain it.”

The law society’s latest statistics come as the regulatory board may change how it approaches issues of diversity, equality and inclusion.

Many of the benchers who were elected in the latest election, on April 30, said they do not support a requirement that lawyers write a Statement of Principles, which says lawyers have an “obligation to promote equality, diversity and inclusion generally, and in your behaviour towards colleagues, employees, clients and the public.”

One of the top vote-getters who opposed the Statement of Principles requirement was Cheryl Lean, who in the 1970s helped start conferences for women and did a photo heritage project on the lives of women during the feminist movement. She went on to help with a national campaign to secure equality rights for women in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Still, during this spring’s bencher election, many candidates touched on issues facing women and racialized licensees in the profession. Candidate Andrea Clarke, based in Guelph, Ont., who was not elected, said her campaign was inspired in part by issues facing women in the profession.

“We’ve done so well for attracting more women to the profession over the years, which is fantastic, but it’s the retention of these women — the attrition rates are high,” she told Law Times in March.

Vicars says the OBA is planning a summit for later this year that will hopefully address some of the concerns raised by women in the profession.

“I think the solution lies in a number of things. What helps women is giving them the tools to help them truly advance in the profession: teaching them the skills they need to negotiate salaries, to speak up for themselves, teaching them how to launch their own practices. That’s something we are doing at the OBA, not just for women but for all genders,” says Vicars. “Those are the types of small steps I’m talking about, to make the practice of law better for everyone.”