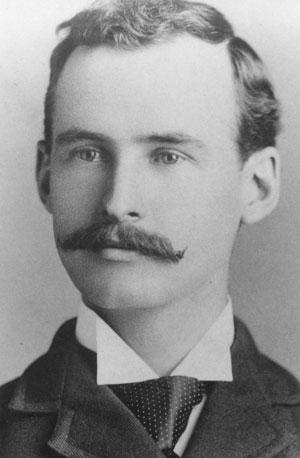

Toronto lawyer Alexander David Crooks tried to comfort himself with the family motto — “perseverando” — when he inherited the biggest case of his career in 1912.

The word means perseverance in Latin. At the time, Crooks had a daunting task ahead and there was family pride at stake.

He would be seeking justice against the American government for a de facto act of piracy committed against his grandfather, James Crooks, and his brother, William Crooks, a century earlier.

The brothers owned a commercial schooner called the Lord Nelson that ferried goods and passengers across Lake Ontario from Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., to the St. Lawrence River.

On June 5, 1812, 13 days before the declaration of the War of 1812, American officials patrolling the lake fired upon and forcibly boarded the Lord Nelson as it was returning to Niagara.

They seized the vessel, which included about $2,000 worth of commercial cargo, and took it to a naval base at Sackets Harbor, N.Y. They outfitted it with 12 cannons, renamed it the Scourge, and pressed it into service against the British when the war started soon after.

The Scourge, along with a fellow ship called the Hamilton, went down during a squall on Lake Ontario the next summer. Fifty-three American sailors lost their lives in the tragedy.

There were only 19 survivors, including Ned Meyers, who had a feeling the vessel would bring bad luck.

For the Crooks brothers, the bad luck continued after the war when they sued the American government for illegal seizure of the ship.

In July 1817, a court in New York state ordered the American government to pay the brothers about $3,000 in reparations.

But when they went to claim the money, they were shocked to learn the clerk of the court, Theron Rudd, had embezzled the funds and fled the country.

He was later arrested and sentenced to 10 years of hard labour. The money was never found.

Despite the setback, James Crooks continued to pursue the matter for the next 43 years until his death in 1860. (William died in 1836).

y this time, James had built a massive commercial complex known as Crooks Hollow near Hamilton, Ont. He was also a justice of the peace and a provincial politician with friends in Ottawa, London, England, and Washington.

He tried every tactic possible, including personal appearances in Congress, to persuade the Americans to do the right thing. He generally got a favourable hearing in the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Two presidents, James Monroe in 1819, and Grover Cleveland in 1886, also urged Congress to honour the claim. But there was always some legal or political sticking point when it came to handing over the money.

The claim lapsed for several years after James’ death. Eventually, his son Adam Crooks took over the file. Adam was a partner in a powerful Toronto law firm that included Nicol Kingsmill, who would later spend almost two decades on the case.

In a report to Cleveland in 1886, a congressional committee complained the case had come to a standstill after the Civil War.

“The petitioners allege it would have been useless to askfor attention to the claim during the excitement of the Civil War,” the president was told.

“The son of Hon. James Crooks, Adam Crooks, became insane and it was not possible to obtain an explanation for non-prosecution of the claim for the last few years.”

Adam, who had been a brilliant solicitor, ended up in an insane asylum in Maryland and died in the United States in 1885.

Alexander David, or A.D. as he was known, first became involved in the claim in 1895 while Kingsmill was chief counsel for William and James’ heirs.

Kingsmill also hired an American lawyer, Col. Charles Lincoln, to press the case in Washington. Lincoln claimed to have influence in political circles and said he’d be able to shepherd the Lord Nelson appropriation bill through Congress.

By this time, however, the heirs were getting increasingly impatient and truculent. A faction in the United States, led by spinster Eva Crooks from Benton Harbour, Mich., was also questioning Lincoln’s honesty and competence.

Upon hearing their accusations, Lincoln wrote that he was thoroughly “disgusted with the whole business” and threatened to sabotage the Lord Nelson bill. “I think I can prevent further action,” he said in a letter to Kingsmill.

Kingsmill also expressed his frustration with the meddling heirs in a letter to A.D. “It is a case of too many cooks spoiling the broth,” he wrote.

He also suggested that Lincoln was capable of causing trouble in Washington if they didn’t pay him promptly.

“If we make an enemy of Colonel Lincoln, there would not be the slightest hope of our getting anything in Washington as long as he chose to prevent it,” Kingsmill wrote in 1901.

In 1906, Lincoln withdrew his threats after he received $100 to get off the case. A.D. became lead counsel for both branches of family — the heirs of William and James — after Kingsmill died in 1912.

By this time, there was a realization that the Lord Nelson bill had no chance in Congress and it’d be better to plead the 100-year-old claim before an international tribunal set up in 1910 to settle outstanding disputes between the United States and Great Britain.

As he was preparing to argue the case, A.D. wrote a memo of talking points reminding himself to mention the family motto in connection with the diligence his ancestors had shown in their quest for justice.

In 1914, the Washington-based tribunal awarded the Crooks heirs $5,000 in damages for the ship and about $19,000 in interest.

After legal fees and other expenses, the genealogical jackpot would be just $15,000 to share among 25 legitimate heirs and their children.

Any elation A.D. might have felt over his legal victory didn’t last, however. As a result of delays caused by the First World War and various diplomatic and legal snarls, nobody got any money until 1930.

Eva, who had campaigned to get rid of Lincoln, became increasingly frustrated at the delays and started directing her invective towards A.D. She often alluded to family squabbles in her letters to her cousin.

“It looks as if you were trying to cheat us of our rights,” she wrote with an unsteady hand on her florist shop stationery in 1929.

“I give you 10 days to get busy and send our money or we will prosecute you. I have your letter and I will give everything to the newspaper, just how and what you have done,” she threatened a few weeks later.

A.D. remained professional and non-confrontational through it all as he tried to explain the delays.

When the cheques finally arrived in March 1930, Eva and her brother, Alfred Crooks, were biggest pickers in the family tree.

They each got $952.46. Others got anywhere from $119.06 to $634.98. As an heir, A.D. got $476.23 as well as a few thousand dollars in legal fees.

“It is great to have at last got this long, drawn-out case settled and I am sorry the amount for division is so small,” he wrote in 1930. He stopped practising law the next year and died in Toronto in 1941.

The Toronto Daily Star described the settlement in almost biblical tones on Feb. 17, 1930.

“The legitimate claimants have been determined, the cheques are in the mail, and justice has been done after 118 years. And so endeth the story of the Lord Nelson.”

The ships, meanwhile, remain in the lake. In August 2013, in fact, U.S. and Canadian dignitaries will hold a ceremony on Lake Ontario near the site of the Hamilton and the Scourge as part of the bicentennial celebrations of the War of 1812.

The word means perseverance in Latin. At the time, Crooks had a daunting task ahead and there was family pride at stake.

The word means perseverance in Latin. At the time, Crooks had a daunting task ahead and there was family pride at stake.