An inquiry into the conduct of Justice Paul Cosgrove will reconvene in the new year after the Supreme Court of Canada denied him the chance to appeal an earlier decision on the right of attorneys general to call for inquiries into a judge’s conduct.

Caroline Collard, senior advisor at the Canadian Judicial Council, says the council is aiming to begin the inquiry into the Ontario Superior Court judge’s conduct as early as possible next year.

The council is not yet sure where the five-member inquiry committee, which includes three judges and two lawyers, will choose to hear the public proceedings, she says, as there is no set place where it has to meet.

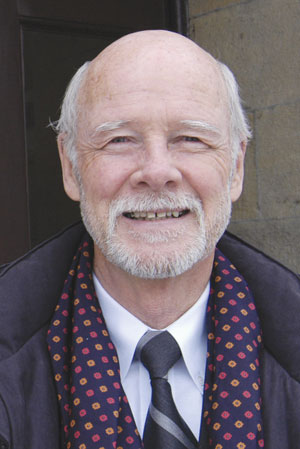

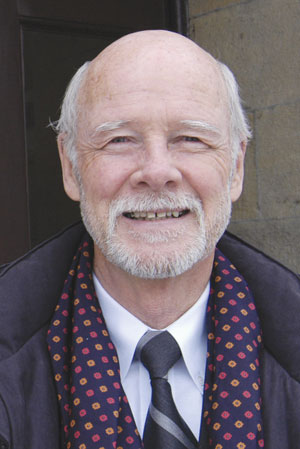

Cosgrove, 72, was appointed to the bench in 1984, and has been based out of Brockville, but has also worked as a travelling judge, spending some time in the Ottawa court.

The Canadian Judicial Council first launched an inquiry into Cosgrove’s conduct nearly four years ago. Former Ontario attorney general Michael Bryant sent the organization a letter in April 2004 requesting an inquiry following Cosgrove’s 1999 ruling in the second-degree murder trial of Julia Elliott in Ottawa.

Cosgrove granted a stay of proceedings in R. v. Elliott, after concluding that there had been upwards of 150 Charter violations, implicating members of Crown counsel and senior members of the Ministry of the Attorney General of Ontario.

He also ordered that the Crown pay her legal costs from the outset of the proceedings.

The Ontario Court of Appeal overturned Cosgrove’s decision staying the charges and the costs order in the Elliott case in 2003 and ordered a new trial, noting that the evidence did not support “most of the findings of Charter breaches by the trial judge.”

The panel also noted that “the trial judge made numerous legal errors as to the application of the Charter,” and “he made findings of misconduct against Crown counsel and police officers that were unwarranted and unsubstantiated.”

While the five-person inquiry committee was appointed to look into Cosgrove’s conduct following the attorney general’s request in 2004, Cosgrove brought an application to challenge the constitutionality of s. 63 (1) of the Judges Act, which allows a provincial attorney general to request an inquiry into the conduct of the judge without the complaint being subject to the Canadian Judicial Council’s usual screening process.

The committee held two days of hearings in December 2004 and unanimously rejected the constitutional challenge.

In other circumstances, when a complaint is made, the judicial council reviews it, and if it falls within the council’s mandate, it is studied in more detail and the judge in question, as well as judge’s chief justice, are sent a copy of the complaint and asked for their comments.

According to the judicial council, “The complaint is often resolved at this stage, with an appropriate letter of explanation to the complainant.” If the complaint is not resolved at this stage, the file can be referred to a panel for further review, who can then either refer it to the next stage - an inquiry committee - or close the file, expressing concern, recommending counseling or other remedial measures.

Cosgrove’s inquiry was put on hold in 2005 as he took the matter to the Federal Court, requesting a judicial review of the committee’s decision. Justice Anne Mactavish ruled that the committee had no jurisdiction to proceed with the inquiry and that s. 63(1) “represents an unjustifiable interference with the independence of the judiciary.”

However, in March, the Federal Court of Appeal set aside the 2005 decision, with the unanimous panel of Justices Karen Sharlow, J. Edgar Sexton, and John M. Evans ruling that the section was constitutional, does not impair judicial impartiality, and is “consistent with Canadian constitutional principles for provincial attorneys general to play a part in the review of the conduct of judges of the superior courts of their respective provinces.”

Last month’s dismissal of Cosgrove’s leave to appeal application by the Supreme Court sends the matter back to the inquiry committee. Cosgrove is being assigned cases at the moment, says his lawyer, Chris Paliare.

Paliare tells Law Times that they were “extremely disappointed” following the decision not to grant leave.

“This is an area of judicial independence that the court, the Supreme Court of Canada, had never looked at in the past. That is, dealing with issues related to the Canadian Judicial Council,” he says.

“We were hopeful that leave would be granted to be able to deal with this interesting constitutional issue,” he adds.

From a procedural standpoint, according to the Canadian Judicial Council, when it has completed its investigation, the inquiry committee will report its findings to the council, which then decides whether or not to recommend to the federal minister of justice that the judge be removed from office, which can only be done after a joint resolution by Parliament.

Caroline Collard, senior advisor at the Canadian Judicial Council, says the council is aiming to begin the inquiry into the Ontario Superior Court judge’s conduct as early as possible next year.

Caroline Collard, senior advisor at the Canadian Judicial Council, says the council is aiming to begin the inquiry into the Ontario Superior Court judge’s conduct as early as possible next year.