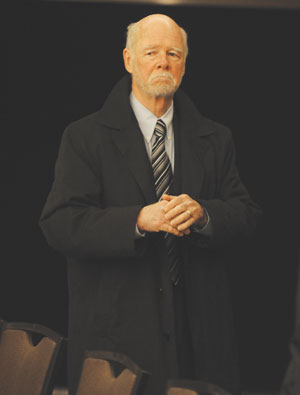

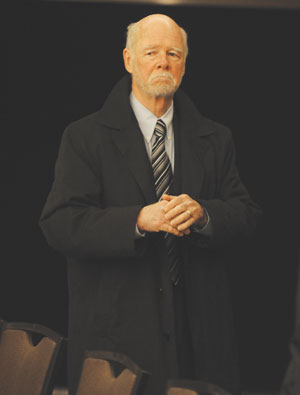

Superior Court Justice Paul Cosgrove resigned late last week thus dodging the dubious distinction of possibly becoming the first judge in Canadian history to be voted out of office by Parliament.

The resignation came three days after the Canadian Judicial Council recommended his ouster to the federal justice minister.

“We find that Justice Cosgrove has failed in the execution of the duties of his judicial office and that public confidence in his ability to discharge those duties in future has been irrevocably lost,” wrote 22 judges from Canada’s superior courts who finalized the matter.

“We find that there is no alternative measure to removal that would be sufficient to restore public confidence in the judge in this case.”

Cosgrove’s lawyer Chris Paliare tells Law Times his client “wants to spend more time with his family and grandchildren, and that he genuinely loved his work and is and was of the view that whatever occurred in the Regina v. Elliott case was all done in good faith by him.”

Paliare says Cosgrove “figured that he’s got six more months to go before he’s 75 and this is not something that he wanted to endure.”

Justice Minister Rob Nicholson said in a release announcing the judge’s decision, “In view of the fact that Justice Cosgrove has resigned, there is no further action to be taken.”

Meanwhile, a specialist in legal ethics and professionalism suggests the council’s decision creates a tenuous approach to weighing the proper outcome of judicial misconduct.

The council decision states, “In this case, it is our conclusion that the misconduct by Justice Cosgrove was so serious and so destructive of public confidence that no apology, no matter its sincerity, can restore public confidence in the judge’s future ability to impartially carry out his judicial duties in accordance with the high standards expected of all judges.”

The council said that a concession from Cosgrove that his actions meant he could not sit on cases involving the provincial or federal Crown acted as a “tacit acknowledgment” that many litigants may not have confidence in his ability to judge impartially.

The council also found that letters of support for Cosgrove do not help determine if public confidence was too deeply undermined by his blunders in a murder trial.

Once the CJC recommended Cosgrove’s removal, the final step would have been a joint resolution of Parliament.

Cosgrove is the second judge the CJC has recommended to the minister of Justice for removal from office. In 1996, it called for the ouster of Quebec Superior Court Justice Jean Bienvenue, who was cited for offensive remarks against women, but he also resigned before the matter went before Parliament.

The 74-year-old Cosgrove, a former federal cabinet minister and mayor of Scarborough who has lived in Brockville since becoming a judge in 1984, would have reached mandatory retirement from the bench in December.

“We’re just very disappointed by the result,” says Paliare, a founding partner of Paliare Roland Rosenberg Rothstein LLP. “I was cautiously optimistic that we would have prevailed. That was my view following the argument.”

Cosgrove declined Law Times’ request for comment on the decision.

University of Toronto Faculty of Law Prof. Lorne Sossin, who teaches ethics and professionalism, says the CJC has set a difficult precedent to uphold with the decision.

“It puts them in the position of having to - and it seems to me just inherently subjective - assess when the apology will restore public confidence and when it won’t. And of course they do this in a completely non-empirical way. They do nothing to assess how the public is in fact reacting; it’s themselves in their radar for this principle of public confidence that’s at issue.

“It introduces an element of uncertainty and challenge for maintaining coherence. And this is a particularly difficult exercise to begin with - deciding when misconduct is significant enough to warrant removal.

But it’s now going to be very difficult to predict, once there’s an apology, whether it is or isn’t going to be sufficient to restore public confidence.”

Sossin says this approach will prove difficult for the CJC to sustain in the long run, particularly as it has previously found apologies to mitigate serious misconduct.

The complaint against Cosgrove was issued on April 22, 2004, by then-attorney general Michael Bryant. That was about two months after the appeal period ended following the Ontario Court of Appeal’s Dec. 4, 2003, decision to overturn a stay of proceedings in the Julia Elliott murder trial, which Cosgrove presided over from 1997 to 1999.

The appeal court found that the bulk of over 150 Charter violations cited by Cosgrove against the Crown were erroneous.

The court found that any relevant Charter violations were taken care of before the trial would have started and that Cosgrove misapplied the Charter, made “unwarranted and unsubstantiated” misconduct findings against the Crown and police, misused his contempt powers, and allowed investigations into areas not relevant to the case.

The appeal court set aside the stay of proceedings and ordered a new trial. Elliott, a Barbados native, subsequently pleaded guilty to manslaughter in the slaying of 64-year-old Larry Foster. She

received a seven-year sentence.

Cosgrove took a constitutional challenge over CJC proceedings in 2005 to the Federal Court. He won that decision, but the Federal Court of Appeal later overturned the lower court decision, and the Supreme Court rejected his leave to appeal application in November 2007.

The CJC inquiry committee resumed in September 2008, and found the following in terms of Cosgrove’s conduct at the Elliott trial:

• an inappropriate aligning of the judge with defence counsel giving rise to an apprehension of bias;

• an abuse of judicial powers by a deliberate, repeated, and unwarranted interference in the presentation of the Crown’s case;

• the abuse of judicial powers by inappropriate interference with RCMP activities;

• the misuse of judicial powers by repeated and inappropriate threats of citations for contempt or arrest without foundation;

• the use of rude, abusive, or intemperate language; and

• the arbitrary quashing of a federal immigration warrant.

Four out of the five inquiry committee members found that the conduct meant that Cosgrove had “rendered himself incapable of executing the judicial office.”

The CJC convened in March 2009 to hear Cosgrove’s response to the inquiry committee’s findings. Paliare urged the council against ousting the judge. He said letters of support for Cosgrove, the fact that he sat as a judge without incident for over four years after the Elliott trial, and a statement of regret and apology should be enough to merit a less serious sanction.

But the council found that, “These errors went far beyond the types of errors that can be readily corrected by appellate courts.”

The resignation came three days after the Canadian Judicial Council recommended his ouster to the federal justice minister.

The resignation came three days after the Canadian Judicial Council recommended his ouster to the federal justice minister.