Employees have new responsibilities in terms of mitigating damages following wrongful dismissal, thanks to a recent Supreme Court of Canada decision, say lawyers.

A 6-1 majority of the top court found that Donald Evans, a business agent for Teamsters Local 31 in Whitehorse, didn’t take the proper steps when during a 24-month notice period he turned down an offer to return to his old job.

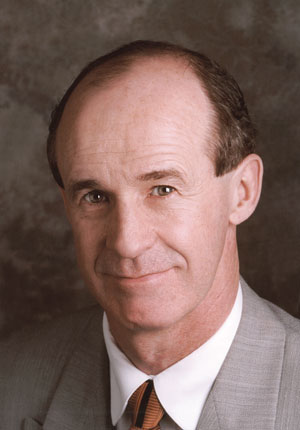

“This is as legally perverse as asking the guy in the electric chair, ‘Would you like AC or DC,’ ” says Eugene Meehan, chairman of Lang Michener LLP’s Supreme Court practice group, who represented the appellant in Evans v. Teamsters Local Union No. 31. “An appropriate analogy, because whether it’s a wrongful dismissal or constructive dismissal, the employee is history.”

Evans spent over 23 years in the position before being fired in January 2003 after the election of a new union executive he hadn’t supported during a campaign, said a set of agreed facts. Evans requested a notice period consisting of 12 months of further employment, followed by 12 months’ severance pay.

The decision will cost Evans most of a $100,000 award he received at trial from Yukon Supreme Court Justice Leigh Gower. Gower found he was wrongfully dismissed and entitled to 22 months’ pay.

The majority decision, written by Justice Michel Bastarache, noted Evans received an offer to return to the position and that he didn’t discuss his concerns about returning to the job during his negotiations with the union following his termination.

“Although the request to return to work should have been drafted differently, Mr. Evans clearly understood that this was a unique position and that he had no work alternative if he were to remain in Whitehorse,” wrote Bastarache. “The request fulfilled the 24 months’ notice that Mr. Evans had offered on Jan. 3, 2003.”

The majority also said that Evans and the incoming union president did not have an acrimonious relationship, and that there was “no evidence that Mr. Evans would be unable to perform his duties in the future. In fact, Mr. Evans had himself suggested that he could continue to perform his work.”

Meehan says the decision signals a shift away from pro-plaintiff decisions, such as Wallace, dealing with punitive damages.

Specifically, Meehan points to the majority’s position that two of Evans’ reasons for not wanting to return to work at the union - that he was terminated without cause and that the termination was planned and deliberate - are “entirely irrelevant.”

Meehan says the majority’s position lacks balance.

“A balanced approach, particularly in wrongful termination cases that are generally so determined by the facts, is where you look at both objective and subjective factors,” says Meehan. “To look at objective factors in isolation from what actually happens on the ground is further suggestive of a move away from pro-plaintiff decisions of the court.”

Meehan adds the decision effectively “abolishes” the court’s prior distinction between wrongful dismissal and constructive dismissal.

“Given that wrongful dismissal and constructive dismissal are characterized by employer-imposed termination of the employment contract (without cause), there is no principled reason to distinguish between them when evaluating the need to mitigate,” Bastarache wrote in the majority decision.

“That in my view is a tectonic turn in determination of employees,” says Meehan.

Justice Rosalie Abella, in her dissenting opinion, noted the union failed to prove that Evans didn’t properly mitigate his damages.

“It was certainly open to the Teamsters to try to prove that Mr. Evans had made insufficient attempts to mitigate the damages they caused,” wrote Abella. “What they were not entitled to do, however, was dictate how he should mitigate them by ordering him back to the workplace from which he was fired.

“The consequence of a refusal to comply with this demand . . . was to be a new firing, this time for cause and therefore without notice. This would - and did - have the bizarre consequence of transforming a wrongful dismissal attracting a substantial notice period to a lawful one attracting none. This result is, in my view, as unpalatable as it is legally and factually unsustainable.”

Abella also said, “Firing an employee without notice, then requiring him or her to return temporarily to work at his former workplace because the unlawful dismissal resulted in bleak employment prospects, has the perverse effect of requiring a wronged employee to ameliorate the wrongdoer’s damages, rather than the other way around.”

Meehan says the majority decision takes a legalistic, inflexible approach to the case, whereas the dissent takes a factual and flexible approach.

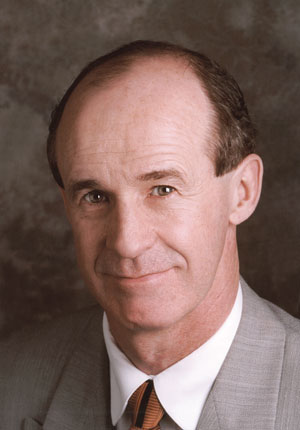

Erin Kuzz, past chairwoman of the Ontario Bar Association’s labour and employment section, says the decision gives employment lawyers some clarity in terms of dismissal expectations.

“My experience is that most employers want to do the right thing, and they often need to have clarified what exactly are those expectations,” says Kuzz. “When those expectations are clear, they do everything they can to meet them.

“To the extent it provides clarity for the community, it helps everybody,” she says.

Constructive dismissal has been a “fuzzy” area for a long time, she says. It has been unclear when a constructive dismissal is triggered, and what the obligations are for both sides, says Kuzz.

“The issue of whether or not an employee has to remain in their employment is a hotly contested one. What the Supreme Court has done here, whether you like the clarity or not, they’ve provided clarity.”

Kuzz, who now practises as an employer counsel, says the decision puts a tighter leash on employees.

“It’s going to make it a little bit tougher for an employee to quit their job and say, ‘You owe me, in this case 24 months notice,’ without there being a particularly downside risk to the employee in taking that course of action. Employees should think twice before claiming their workplace environment is so bad that they can’t continue to work there anymore.”

Meehan says “the chances are high” the decision will be revisited.

“That is because an unscrupulous and overly strategic employer may be tempted to use a bait-and-switch tactic, in the sense that, you fire an employee, you force the employee to suffer the humiliation, alienation, and perceived public disgrace of being fired, and then you offer them back the same job, and when they tell you - politely or impolitely - where to put that, the employer now has the defense of mitigation.

Which means that the employer walks scot-free, though being a Scot myself, I’ve never really liked that phrase.”

A 6-1 majority of the top court found that Donald Evans, a business agent for Teamsters Local 31 in Whitehorse, didn’t take the proper steps when during a 24-month notice period he turned down an offer to return to his old job.

A 6-1 majority of the top court found that Donald Evans, a business agent for Teamsters Local 31 in Whitehorse, didn’t take the proper steps when during a 24-month notice period he turned down an offer to return to his old job.