That's History

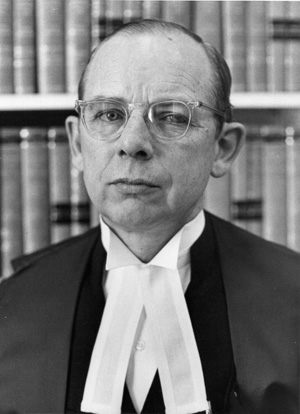

John Douglas Arnup, one of the great

Born in 1911, the son of a Methodist minister

and moderator of the United Church of Canada, Arnup learned law in one of the

great litigation firms, Mason Foulds (WeirFoulds today) and he joined that firm

when he was called to the bar in September 1935 — just 70 years ago.

Born in 1911, the son of a Methodist minister

and moderator of the United Church of Canada, Arnup learned law in one of the

great litigation firms, Mason Foulds (WeirFoulds today) and he joined that firm

when he was called to the bar in September 1935 — just 70 years ago.

At Mason Foulds, Arnup got a rigorous

apprenticeship with Gershom Mason, Roy Kellock, Bill Gale, and others. He later

said that it was seven years before he took a case to the Supreme Court of

Canada — but when he did, he did it right, because of the Mason Foulds

training.

After war service in

Arnup did countless cases in many courtrooms.

One of his great cases, fought between 1966 and 1968, was Leitch Gold Mines v.

Bertha Wilson, who also had a role in the case,

called it "

There were masses of technical evidence to

assimilate, but a crucial factor was the credibility of the plaintiff's key

witness. Arnup's successful demolition of that credibility gave him the win.

Popular and respected from early in his career,

Arnup became a bencher at age 40 when most benchers were a good deal older. He

had an extraordinary impact at the Law Society of Upper Canada. He was deeply

involved in the remaking of legal education in the 1950s, in the moving of

In 1970, chief justice George Alexander Gale of

the Ontario Court of Appeal told Arnup, "If I can get you, I can get anybody,"

and Arnup, soon joined by luminaries such as Charles Dubin, Bud Estey, and

Arthur Martin, helped build the court into one of the strongest in

Retirement in 1985 allowed him to expand his

other career as chronicler of his profession. He wrote many essays, some on

substantial issues, some simply colourful stories, for The Law Society Gazette.

He wrote a biography of a personal hero, justice William Edward Middleton. He

struggled for years to bring into being a history of the Court of Appeal.

A decade ago, I was writing the bicentennial

book Law Society of Upper Canada and

Instead he insisted I call him John and said

very firmly the book was my responsibility and he was merely interested and

eager to help. Then he proceeded to give my rough draft an extraordinarily

vigorous, careful, and useful critique. If this law thing had not worked out,

he could have been a very fine editor.

But he read the chapters in chronological

order, and I grew nervous again as we approached the era he knew from personal

experience. When Arnup told me he thought I'd got the feel of those times just

about right, it seemed as fine a professional compliment as I'd ever received.

I only knew John Arnup in his 80s and 90s, and

he seemed the nicest man you could imagine. Considering his career, I realized

that in his day he must have been able to be tough, to put work ahead of all

else, to be ruthless in court or convocation.

Doubtless he did. But to prepare this piece I

looked over many years' worth of recollections of John Arnup. Seems just about

everybody has emphasized what a nice guy he was.

Christopher Moore's most recent book is

McCarthy Tétrault: Building Canada's Premier Law Firm, just published by

Douglas & McIntyre. His website is www.christophermoore.ca