Loopholes in a decision by Canada’s top court to ban potential parents from paying surrogates and donors for their eggs, sperm, and embryos have sparked a rise in the number of illegal private agreements and international deals across the country, a University of Manitoba law professor said last week.

Karen Busby made the comment as the

Assisted Human Reproduction Act enters its eighth year amid criticism by legal experts who say the federal regulation aimed at making “the health and well-being of children born through assisted human reproductive technologies a priority” has become “confusing” and “complicated.”

“It’s a kind of never-never land now where the federal government doesn’t pass regulation and the provinces have only moved forward in areas where they think it’s needed, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing provincially,” says Busby. “In the end, though, the reality is people are making private agreements in spite of this and they are getting paid.”

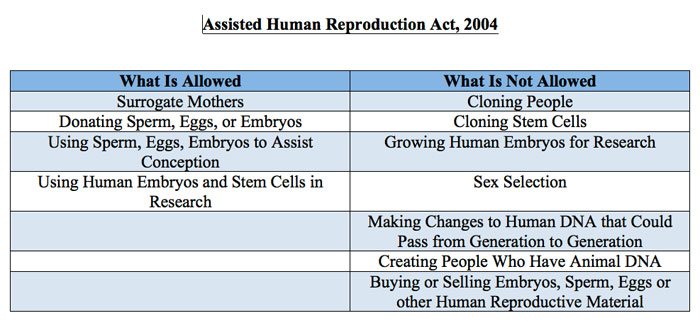

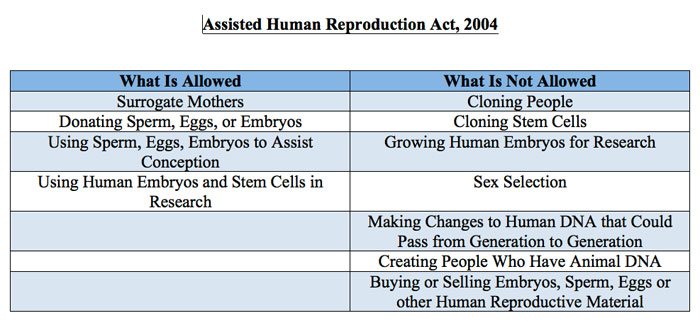

Canada created guidelines for surrogacy in 2004 with the Assisted Human Reproduction Act — making it illegal to offer to pay a surrogate or for eggs, sperm, or embryos. It also required all surrogates to be 21 or older and made it illegal to accept payment for arranging a surrogacy. Penalties range from a maximum fine of $500,000 to 10 years in jail or both.

In the same breath, the act also makes it illegal to clone people, clone stem cells, grow human embryos for research, participate in sex selection, create people with animal DNA, and make changes to human DNA that would pass from one generation to the next.

In 2008, the Quebec government successfully argued that parts of the act violated the right of provinces to regulate health care. The federal government eventually appealed that ruling, and in April 2009 the case went before the Supreme Court of Canada. Quebec maintained that it supported parts of the law, like the banning of human cloning, but argued that infertility treatments fell under provincial jurisdiction. The province was supported by Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, and Alberta.

In 2010’s Reference re

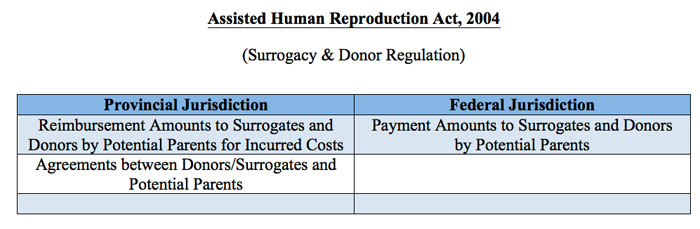

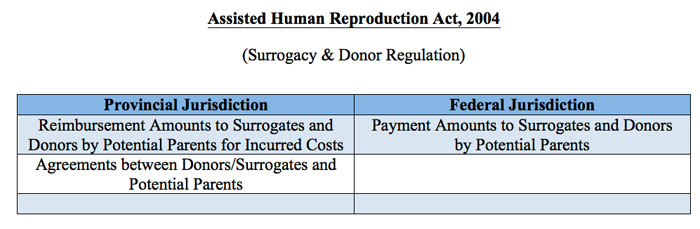

Assisted Human Reproduction Act, the Supreme Court eventually granted provinces the exclusive authority to regulate fertility clinics, license doctors, reimburse sperm and egg donors for their expenses, and decide the number of allowable embryos to implant. In the split decision, the Supreme Court also ruled the federal government still had the power to ban paid surrogacy, as well as the use of underage donors and the commercial trade of eggs, sperm, and embryos.

Yet, it’s a move that has placed a heavy burden on lawyers trying to ensure their clients meet both federal and provincial regulations and has ultimately added to confusion about the law rather than clarified it, argues lawyer Sara Cohen.

“Right now, as it stands, you can’t pay a surrogate, but you can reimburse them,” says Cohen, a partner at Raviele Vaccaro LLP. “But, because there is little to no regulation provincially, lawyers are left to rely solely on common sense about what should and shouldn’t be considered reimbursable, which can fluctuate from lawyer to lawyer.

“It becomes really difficult to talk to clients who may have been searching for a donor or a surrogate for so long, and are understandably emotional, and to have to say to them, there’s no case law or regulation, we’re in a grey area now, is heartbreaking.”

According to

Assisted Human Reproduction Canada, a federal regulatory agency, this was far from the act’s original intention.

“Canadians told us in consultations leading up to the creation of the Act that the commercialization of the human reproductive capacity is not in keeping with Canadian values,” AHRC said in a notice. “Just as the commercialization of body parts is not allowed, neither is the purchase or commercial profit of sperm and eggs.”

Under the act, AHRC noted, “no payment can be made to sperm or egg donors for their donation. However, recognizing that donors may incur expenses in making a donation, the Act does allow for the reimbursement of reasonable expenditures if done with a license and according to regulations. These regulations are currently being developed, and until they are finalized, donors may be reimbursed for an amount up to their actual expenditures.”

But a lack of regulation provincially and conflicts with federal law if regulation does exist, has created an undue burden on large segments of the population in the meantime and focuses largely on the possible negative effects of the law rather than the positive, argues Cohen.

“In vitro fertilization is so common now,” says Cohen. “Nearly one out of every six couples deals with infertility; so the federal regulation really seems outdated and not really in line with the general population’s comfort level in my opinion. There are often people suffering from cancer for example, that can’t have children themselves, and these are just some of the people that we want to help, but making it a criminal law to do so really seems to dissuade people.”

In the meantime, the recent federal regulation has also caused an unintended ripple effect across the country, says Busby, creating international deals between surrogates and sperm donors this year that have left both surrogates and the federal government vulnerable.

“More people are coming from other countries now to look for surrogates in Canada because they know there will be no cost associated with the surrogate’s health care,” adds Busby. “In my opinion, that’s something the government should really be aware of and potential parents should pay those costs.”

The regulation has also had a similar impact on sperm donation, adds Cohen, who notes the number of Canadians donating sperm has decreased significantly since the regulation’s introduction.

“While it is illegal to pay a sperm donor in Canada, it is legal to pay a sperm bank for the altruistically donated sperm,” says Cohen. “Further, it is legal to pay for imported sperm that was paid for in the U.S. In my opinion, this doesn’t really make sense and is just putting unnecessary impediments in the way when the end result is the same: Canadians are paying for sperm for which the donor was paid.”

According to AHRC, the estimated demand for sperm in Canada during February of last year was 5,500. The estimated supply: 60 men. By September, nearly a year after the Supreme Court’s reference, that number had dipped to 35.

Yet, provincial regulations in the future could potentially help ease these unintended consequences, as well as lawyers and physicians who are willing to sit down with the government to discuss these and other effects of the act in the upcoming year, legal experts add.

“It seems to me that a lot of this could be dealt with provincially,” says Cohen. “From my understanding, politically, there may not be the appetite right now, particularly on a topic that creates so many different reactions in people, but that doesn’t mean that it is any less necessary.”

Karen Busby made the comment as the Assisted Human Reproduction Act enters its eighth year amid criticism by legal experts who say the federal regulation aimed at making “the health and well-being of children born through assisted human reproductive technologies a priority” has become “confusing” and “complicated.”

Karen Busby made the comment as the Assisted Human Reproduction Act enters its eighth year amid criticism by legal experts who say the federal regulation aimed at making “the health and well-being of children born through assisted human reproductive technologies a priority” has become “confusing” and “complicated.” In 2010’s Reference re Assisted Human Reproduction Act, the Supreme Court eventually granted provinces the exclusive authority to regulate fertility clinics, license doctors, reimburse sperm and egg donors for their expenses, and decide the number of allowable embryos to implant. In the split decision, the Supreme Court also ruled the federal government still had the power to ban paid surrogacy, as well as the use of underage donors and the commercial trade of eggs, sperm, and embryos.

In 2010’s Reference re Assisted Human Reproduction Act, the Supreme Court eventually granted provinces the exclusive authority to regulate fertility clinics, license doctors, reimburse sperm and egg donors for their expenses, and decide the number of allowable embryos to implant. In the split decision, the Supreme Court also ruled the federal government still had the power to ban paid surrogacy, as well as the use of underage donors and the commercial trade of eggs, sperm, and embryos. “Right now, as it stands, you can’t pay a surrogate, but you can reimburse them,” says Cohen, a partner at Raviele Vaccaro LLP. “But, because there is little to no regulation provincially, lawyers are left to rely solely on common sense about what should and shouldn’t be considered reimbursable, which can fluctuate from lawyer to lawyer.

“Right now, as it stands, you can’t pay a surrogate, but you can reimburse them,” says Cohen, a partner at Raviele Vaccaro LLP. “But, because there is little to no regulation provincially, lawyers are left to rely solely on common sense about what should and shouldn’t be considered reimbursable, which can fluctuate from lawyer to lawyer.