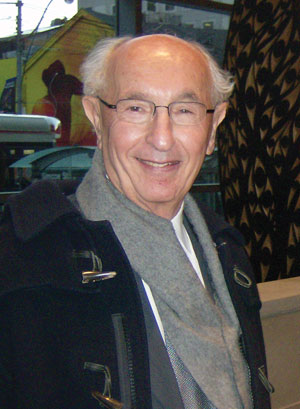

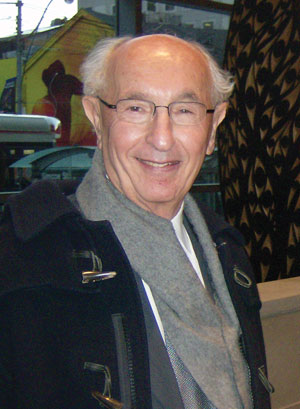

A Superior Court judge facing potential ouster over allegations he was biased while hearing a case involving the City of Toronto says that, while in hindsight he regrets his actions, he did what he thought was best at the time.

Justice Ted Matlow also told a Canadian Judicial Council Inquiry last week he believes judges have only themselves to rely on as a moral compass.

The rare hearing arose after City of Toronto solicitor Anna Kinastowski filed a complaint in 2006, after Matlow sat, in 2005, on a three-judge panel that unanimously ruled against a city proposal for a streetcar right-of-way on St. Clair Avenue.

The allegations of bias stem from the veteran judge’s involvement in a community organization called Friends of the Village, a group that opposed a development, known as the Thelma project, that was planned for an area near Matlow’s home and first proposed by the City of Toronto and a developer in 1999.

“I didn’t do anything that was designed to achieve an improper purpose,” Matlow told the hearing.

Matlow said he read several documents dealing with judges’ ethical responsibilities prior to hearing the case involving the city’s St. Clair streetcar proposal, known as the SOS case.

In cross-examination from the inquiry’s independent counsel Douglas Hunt, Matlow said he “likely looked at” a book, published in 1998 by the CJC, that outlined ethical principals, but that he didn’t necessarily read it from “cover to cover.” Hunt noted the book was published around the time a new advisory body was created for judges to query regarding ethical concerns.

Matlow said he didn’t feel it was necessary to seek advice from that body, as “every judge has to use his own discretion,” or would otherwise be seeking advice “10 times a day.” He noted that judges in Canada aren’t bound by a specific code of ethics, and that he was unaware of any requirement to seek advice.

Matlow said he knew that, by sitting on the SOS case after speaking out against city actions on another development project, he was doing something most judges wouldn’t. But he said he wanted to “fulfill my own concept of a decent human being and judge.”

Matlow said he made an “error in judgment” in sitting on the SOS case, but not an error in law. He added he’s made other errors as a judge, and said, “That’s what appeal courts are for.”

Matlow did not tell his fellow judges or counsel in the SOS case of his involvement with Friends of the Village. He said that in his opinion the SOS case bore no similarities to the Thelma project; therefore, he saw no reason to recuse himself or suggest that it may be necessary.

But he added that, if asked, he likely would have stepped aside. He also believed that counsel for the city in the SOS case knew of his involvement in the Thelma project, and that if they had had any concerns regarding his sitting on the case, they would have expressed them beforehand. Matlow also sat, since 2002, on five previous cases involving the city - four of which resulted in favourable rulings for the city - and his impartiality was never questioned.

Matlow asserted his impartiality toward the SOS case: “I had no views about the merits of it . . . I didn’t care at all what was going to happen.”

However, Matlow admitted that he has since reconsidered his decision to hear the case.

“I’m persuaded . . . that I made errors in how I handled the SOS case,” he said.

First, he said he should not have given documents to the Globe and Mail relating to his criticism of the Thelma project - and specifically of the City of Toronto’s legal department - on Oct. 5, a day before he began sitting on the two-day SOS case. “In retrospect, I wish I just cut off my contact with [Globe and Mail columnist] John Barber,” Matlow said. He added that he could see how the “optics” of that act would lead someone to question his impartiality in the SOS case.

Matlow told the committee that, as far as he was concerned, his fight over the Thelma project ended in February 2004. “I had as much as I could take in my lifetime,” said Matlow.

However, he said a report on the MFP computer-leasing scandal at the City of Toronto, released just before the SOS case began, prompted him to reignite his discussions with Barber regarding the Thelma project. Matlow said he was “struck by the similarity” between the Thelma project and MFP. “It was exactly the same as what we encountered,” he said.

Matlow said he was unhappy only with the actions of city lawyers on the Thelma project, not with those of councillors, who he said are too busy and must rely on the advice of others.

“I couldn’t let the role of the two people in the legal department go,” he said.

Matlow said he now sees how it would have been best for him to have asked counsel, at the outset of the SOS case, to make submissions on whether he was fit to sit on the panel.

“In retrospect, I wish I didn’t participate in SOS,” Matlow said.

Matlow said that at the time his opinion on whether he should sit on the SOS case was shaped by a belief that he could have problems with the city in which he lived - on issues as wide ranging as garbage pickup to development - without tainting his impartiality. He said he felt he was helping the city by uncovering the “problems” surrounding the Thelma project, and therefore was not in conflict with it.

Matlow, a supernumerary who hasn’t been sitting on cases since April 5, 2007, also told the committee that he is “very proud to be a judge” and hopes to return to the bench. He apologized for any problems his actions have caused.

Matlow said the ordeal has been very hard on his family, adding that his own health and disposition has been affected. But he said, “It’s also important for me to be true to my own conscience.

. . . My motives were clean; I thought I was doing the right thing.” However, it turned out to be “a colossal failure,” he said.

While acknowledging that his actions likely caused some damage to the public’s perception of the administration of justice, Matlow said, “I hope if there are such people . . . that there are also people who will think more highly of the administration of justice and applaud what I’ve done.”

The committee will report its findings to the CJC, which will then decide whether to recommend to the federal minister of justice that Matlow be removed from the bench. A judge can only be removed from office following a joint resolution of Parliament.

Justice Ted Matlow also told a Canadian Judicial Council Inquiry last week he believes judges have only themselves to rely on as a moral compass.

Justice Ted Matlow also told a Canadian Judicial Council Inquiry last week he believes judges have only themselves to rely on as a moral compass.