The number of women in federal prisons could go up with the abolition of early parole provisions by the federal government, according to a University of Toronto criminology professor.

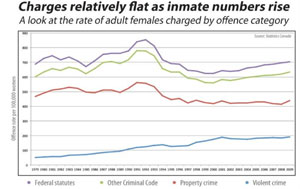

The number and proportion of female inmates had been increasing in both provincial and federal prisons even before the parole changes. According to Statistics Canada, for example, they made up 12 per cent of admissions to remand, sentenced custody, and other temporary detentions in 2008-09. That’s up from 10 per cent in 1999-2000.

And with the end of the federal accelerated parole system, the numbers could go even higher, says Kelly Hannah-Moffat, a professor and director of the Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies at U of T.

“The accelerated parole release had a criteria for eligibility of [the sentence] being your first federal sentence and there are higher proportions of women who are incarcerated for the first time federally,” she says.

Having a history of non-violence, another eligibility requirement under the jettisoned provisions, is another factor that was particularly relevant in cases involving women offenders, according to Hannah-Moffat.

The increase in the number of women in prison has meant increased pressure on both the correctional system and the inmates themselves, she adds. “It means there’s less access to services, less access to programming,” she says.

“And usually when you have people in small spaces, it increases tension and stresses people who are living there — the prisoners and the staff. It makes every daily task more difficult to do.”

According to Kim Pate, executive director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, the upward trend in the women’s prison population began as long as 15 to 20 years ago with the opening of new regional institutions for women.

“The fact that we had six institutions open up across the country meant that we predicted, sadly correctly, that . . . we might see an increase in the number of women who are being given federal sentences or are seeking federal sentences because their lawyers or Crown prosecutors thought there would be more rehabilitative opportunities in the new prisons,” she says.

Although overcrowding at prisons affects both men and women, it’s “experienced differently” by women, says Hannah-Moffat. “One of the issues is that we know that there’s a large portion of women in custody who have children . . . and women in custody tend to be the primary caregivers of those children,” she says, adding there will be “collateral consequences” for the children of women who have gone through the correctional system.

“There’s very limited opportunity to bring the child into custody, particularly if they’re a very young child and there are very limited opportunities to visit those children,” she says. She notes women often end up at institutions far away from home, something that makes it difficult to maintain relationships with their children.

According to Pate, statistics out of the United States have shown 90 per cent of the children whose mothers go to prison end up in the care of the state. That number is just 10 per cent for children whose fathers leave to serve time. The numbers, she suspects, would be comparable to Canada’s.

A mother-child prison program launched by the federal government in Canada has seen little participation. The program, which allows women inmates to bring their children into institutions, has stringent eligibility requirements almost akin to the ones needed for regaining custody of a child through social services, says Pate.

“Paradoxically, people who might be excellent parents and excellent mothers, they’ll never have access. And those who do have access, it may actually cause them to come to the attention of social services in a way that’s completely unwarranted because of the level of assessment.”

The high prevalence of mental-health issues among women in custody only adds to the problem. According to the Correctional Service Canada, 29 per cent of women offenders in federal custody were identified at admission as presenting mental-health problems, a proportion that has more than doubled since 1996-97. The Office of the Correctional Investigator has also reported that women tend to harm themselves more than men in prison.

Despite of these numbers, there’s a lack of understanding of mental illness and how it affects women in prison, says Hannah-Moffat. And while men often have an opportunity to go to institutions with specialized psychiatric facilities, women tend not to benefit from such resources as there are a limited number of prisons available to them, she says.

“Women tend to be a risk to themselves more than others. The issue of self-injury, for example, it looks different in men and women’s institutions,” says Hannah-Moffat.

And unlike some male inmates who enjoy the support of relatives in the community, studies show the favour is “not reciprocated” for women, says Hannah-Moffat.

Pate, who’s in regular contact with women in prisons, says the support issue is one of the top concerns she hears. Instead of more programs, she says a look at why women are going to jail in large numbers would be helpful.

According to Statistics Canada, 22 per cent of women in provincial prisons were there for violent offences while 23 per cent were in custody for property-related crimes in 2008-09.

“We should really examine why imprisonment is being used so liberally [with women] when in fact their risk to public safety, the need for corrective action or any of the other sentencing principles really could be called into question,” says Pate, who notes women as a group are the least likely to reoffend and more likely to reintegrate safely into the community.

“It really is emblematic of women’s inequality in this country that the poorer, more racialized, more disabled [you are], the more likely you are to come under the gaze of the state and more likely to be criminalized and institutionalized,” she adds.

As Canada’s penitentiaries begin to overflow, a four-part Law Times series this summer will look at the issue of remand and other trends within the correctional system in Canada. Using data from various reports, the series will explore why more people, including women, are ending up in jail even as crime rates go down.

For more from the series, see "

Reliance on sureties boosting Ontario remand numbers" and "

Prison segregation rising."

The number and proportion of female inmates had been increasing in both provincial and federal prisons even before the parole changes. According to Statistics Canada, for example, they made up 12 per cent of admissions to remand, sentenced custody, and other temporary detentions in 2008-09. That’s up from 10 per cent in 1999-2000.

The number and proportion of female inmates had been increasing in both provincial and federal prisons even before the parole changes. According to Statistics Canada, for example, they made up 12 per cent of admissions to remand, sentenced custody, and other temporary detentions in 2008-09. That’s up from 10 per cent in 1999-2000. According to Kim Pate, executive director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, the upward trend in the women’s prison population began as long as 15 to 20 years ago with the opening of new regional institutions for women.

According to Kim Pate, executive director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, the upward trend in the women’s prison population began as long as 15 to 20 years ago with the opening of new regional institutions for women.