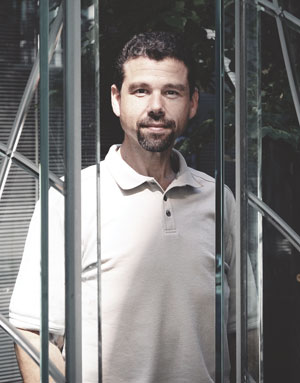

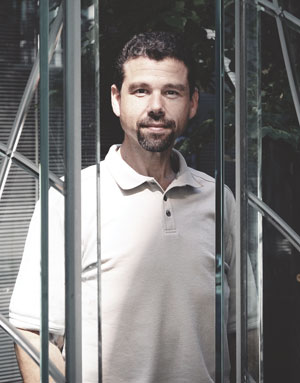

As a successful legal professional, former attorney general Michael Bryant struggled to accept that he was an alcoholic.

“I constantly fooled myself into thinking that because I was functioning as a lawyer, I wasn’t necessarily an alcoholic,” he tells

Law Times.

“My experience was a lot of self-delusion that was eventually followed by a surrender. There is a point where every alcoholic throws their hands up and says, ‘I have to give up this fight.’ That was the turning point for me.”

In fact, Bryant’s addiction to alcohol loomed over his work and personal life for more than a decade but he says that even when he began to admit to himself that he was an alcoholic, he struggled to tell anyone else.

That all changed last month when Bryant released his memoir about his deadly encounter with cyclist Darcy Allan Sheppard and his battle with alcoholism in

28 Seconds: A True Story of Addiction, Tragedy, and Hope.

In the book, Bryant describes his battle with alcohol as something that left him “miserable and paranoid” until he hit rock bottom, woke up one morning six years ago after a night of heavy drinking, and realized he could no longer control his addiction.

Alcohol, Bryant writes in his memoir, had become the most important thing in his life.

According to Bryant, he’s been sober ever since that turning point.

Doron Gold, case manager at the Ontario Lawyers’ Assistance Program, says denial often plays a large role in alcohol dependency among lawyers.

“Often, lawyers who abuse alcohol think of it as a victimless crime,” says Gold.

“They are hesitant to get help and often it’s only when they are on a precipice that they realize they need help. Hovering over all of it is this idea that they are lawyers. They believe they can fix anything and if they admit they have a problem or show that they are having a problem, they believe they’ll be seen as weak. They think they don’t have the luxury of having feelings. So they won’t tell anyone and will try to hide the problems that come from it because they’ve been trained to solve problems.”

Jill Fenaughty, another case manager at the Ontario Lawyers’ Assistance Program, notes that working long hours, the pressures of billing, and high-conflict work environments can also contribute to the stress that sends some legal professionals looking for a release.

“Many lawyers use alcohol as a coping mechanism as it is readily available, quick, and effective at reducing stress and pain,” says Fenaughty.

“Moreover, consuming alcohol at celebratory dinners, after corporate closings, and after a win or loss of a trial is part of the legal culture.”

Still, Bryant says that for an alcoholic, being in the legal profession likely doesn’t help or harm the addiction.

“It’s an addiction,” says Bryant.

“It was always there.”

In Ontario, roughly nine per cent of the calls to the Ontario Lawyers’ Assistance Program relate to alcohol dependency.

At the same time, it estimates that at least 20 to 25 per cent of legal professionals have alcoholic tendencies.

Criminal lawyers, family lawyers, and some judges are particularly susceptible because they often face repeated exposure to the traumatic experiences of clients, says Gold.

“Criminal lawyers, family lawyers, and some judges tend to hear some pretty horrific things on a day-to-day basis,” he says.

“It scars their psyche as if they had experienced the trauma themselves. Some handle it by using alcohol to tranquilize themselves.”

The result, Fenaughty adds, can vary from lawyer to lawyer.

“High-functioning lawyers may be skilled at managing and hiding their excessive use of alcohol,” she says.

Fenaughty notes lawyers with dependency issues will frequently change law firms first in the city where they’re currently practising and ultimately may move elsewhere.

Other high-functioning alcoholic lawyers who are sole practitioners carry on their lifestyle until they ultimately have a medical event like a stroke or their organs begin to fail.

When that happens, Fenaughty says, their family members usually wind down their practice.

Other high-profile lawyers prefer to leave town to protect their reputations, she adds.

But the secrecy surrounding alcohol dependency in the legal profession may be due in part to the way the profession views and interacts with itself, says Gold.

“A lot of the callers we get often think they are the only one struggling with alcoholism. I think that may be because no one is really talking about it. So you end up with lawyers who think they are failures compared to everyone else, which is just not true.”

In the meantime, Canadian Bar Association chief executive officer John Hoyles says the real question lies in how the profession will break the stigma around mental-health issues.

“On the psychological side, it’s an area where more work needs to be done,” says Hoyles.

“Support early on is so important because it can happen where you leave it so long that a person ends up doing something drastic."

To answer this week's poll question related to this issue, see the Law Times

homepage.

“I constantly fooled myself into thinking that because I was functioning as a lawyer, I wasn’t necessarily an alcoholic,” he tells Law Times.

“I constantly fooled myself into thinking that because I was functioning as a lawyer, I wasn’t necessarily an alcoholic,” he tells Law Times.